Foreword - Alice Wiseman, Gateshead Director of Public Health

This report includes descriptions of difficulties with trauma, mental health, drug and alcohol use disorders, and deaths caused by alcohol, drugs and suicide. There are anonymised recordings and quotes of real experiences by people who have been affected. We understand that this may be difficult to hear and read.

If something you hear or read connects with you in a difficult way or brings up strong feelings, please know that you are not alone, and support is available.

Welcome to my 2024 annual report as Director of Public Health for Gateshead. Before I start, I want to highlight that the topic of this report has been very challenging to write so I understand it will be very difficult to read. However, this is something we need to talk about as it impacts many people across Gateshead, in very different ways.

In case anyone feels they need additional support; we have provided some links to support services. Please do reach out and don't suffer alone.

Lives lost too soon

The report addresses an issue of profound importance: the devastating toll of deaths caused, in Gateshead, by drugs, alcohol and suicide.

Too many lives in Gateshead are cut short because of alcohol, drugs and suicide. Sadly, we are seeing increasing harm, particularly in relation to drug related deaths. Deaths of this nature are both a consequence and cause of health inequalities. Whilst harm from alcohol, drugs and suicide can affect everyone, those in our most disadvantaged communities are hardest hit.

Hearing from people with lived experience

Numbers and data are not enough to understand this issue properly. Behind each number is a story of lives lost too soon, of loved ones left behind, and of communities grappling with pain and loss - the ripple effects are far reaching - an issue cutting across families, communities, and wider society.

My purpose in writing this report is not only to illuminate the urgent need for change while honouring the humanity which sits behind the data. Threaded through the report are the voices and experiences of people with lived experience.

It is critical that we give those affected the opportunity to share their story and to hear their voice. To understand the journeys they have experienced, and to heed their messages of hope. The need to work together with those who have lived experience to ensure that our plans and services put people and families at the heart of what they do.

Stigma

We have heard how these deaths may evoke feelings of shame, stigma, anger and guilt, adding to the pain and loss of those left behind. We need to address this stigma head on, and we need to understand how the language we use, often without realising, affects the care giver, deter help seeking behaviour and increase isolation.

The need to challenge stigma and reframe our messages around this issue, removing any blame from individuals and instead, acting on the factors that lead to these experiences and inequalities.

Influences

Harm and death by alcohol, drugs and suicide are influenced by a range of complex factors at a societal, community and individual levels including, poverty, inequality, childhood experiences, insecure work and unemployment, homelessness, social and cultural norms (including gender norms), commercial determinants such as alcohol, gambling and social media, relationship break down, domestic abuse and access to services.

Finally, the experience of death, loss and grief is, in itself, a determinant of health, for those bereaved by alcohol, drugs and suicide, the impact may be even greater. There is a need for support after bereavement, and a compassionate town approach to help recognise this, and mitigate the impacts.

Prevention

We need to focus on prevention by continuing our commitment and drive in delivering the Health and Wellbeing strategy, taking action across the eight policy objectives.

Support and recovery

We need to recognise the importance of services in reducing harm and helping people to recover, but the need to ensure we push further upstream in addressing root causes that create the circumstances which make people more vulnerable to these harms.

Conclusion

The challenges we are facing touch us all in some way, reminding us of the urgent need for compassion, understanding and action.

The report aims to set out the complex web of factors driving these tragedies, highlight the hope we have for something different and the action we need to take to get there.

While the path forward is not without challenges, its one paved with hope, hope that together we can create a future where fewer lives are lost and where prevention, support and healing are accessible to all.

To those who have been affected by this, and those who have generously and bravely shared their stories, we see you, we hear you and we stand with you. It is in your honour that we will continue this critical work.

Our lived experience (lived experience stories)

Lived Experience involvement in this report

People with lived experience have an important role in shaping programmes, interventions and services. The phrase "Nothing about us, without us" highlights the importance of engaging people with lived experience (1). Their insights help address challenges and inequalities in our communities, requiring us all to work together from service commissioners, to providers, and lived experience organisations (2).

In Gateshead, people with lived experience are at the heart of our drug and alcohol services, including roles like peer supporters and recovery ambassadors. Recognising the link between addiction and mental health, mental health peer support roles are embedded in these services, offering visible hope for recovery.

Through focus groups and interviews, we heard from those impacted by alcohol, drugs and suicide, including bereaved families and individuals who faced related challenges such as poor mental health and homelessness. Each person's experiences were unique, but there were often similarities, especially around the stigma they faced. Whilst the views shared may not reflect everyone, the focus groups and interviews aimed to hear from a diverse range of experiences and communities. Throughout this report, you will see these views and experiences shared.

These conversations brought to light personal stories of struggle and resilience. While we present data about the impact of alcohol, drugs and suicide in Gateshead, we also share these real stories to amplify the voices of those affected. Though discussions were often emotional and challenging, people valued the opportunity to share their experiences and be heard. This process highlighted the importance of considering how language shapes understanding and impacts individuals and communities.

We were told how negative, stigmatising language can create feelings of shame and isolation, while positive language made people feel cared for and understood.

Language to use when talking about this topic put forward by lived experience participants

Our Language Matters

Whether you're texting a friend, posting on social media or talking with colleagues at work, the way we communicate about alcohol, drugs and suicide can have an impact on ourselves and our communities.

Making sure you do so safely and responsibly can reduce the stigma about alcohol, drugs and suicide, including suicidal feelings and behaviours, and encourage people to ask for help.

The way we describe people with lived experience matters. As such, the language we have used throughout this report has been chosen with careful consideration of guidance from organisations including the NHS and Samaritans.

Therefore, we ask that all terminology should be replicated exactly in any communications, including media coverage, about this report.

Most importantly, we hope the language used in this report helps anyone who has struggled to find the words to talk about alcohol, drugs and suicide to feel more confident to speak out, fight stigma and empower people to seek support.

Introduction

In Gateshead, lives are being cut short by health inequalities. Those in our most disadvantaged communities face shorter lives and in poorer health. Each life lost affects not just the individual but ripples through families and communities. Tragically, many of these deaths are due to alcohol, drugs and suicide, and may bring complex feelings of stigma, shame, and guilt that deepen the pain.

The ripple effect from people that were affected, you're talking about the whole street. My immediate family, my sister, my husband, my children, my sister's children, me, auntie and uncle, my cousin, even the first responders, you know, everybody that was involved has been affected.

Between 2019 and 2021, 46,200 people in England died due to alcohol, drugs and suicide - an average of 42 lives lost every day (3). In Gateshead alone, 239 residents died during this period, about 80 people per year. The North and coastal areas experience higher rates of these deaths compared to other parts of England (3).

For adults under 50 in Gateshead, alcohol, drugs and suicide are leading causes of death (4). Researchers refer to these deaths as "Deaths of Despair", reflecting the emotional and mental distress behind them. This term originated in the United States in 2015 and highlights rising mortality linked to alcohol, drugs and suicide, particularly among middle-aged people (5). Studies suggest these deaths are tied to social and economic conditions (3), and alcohol and drugs themselves are significant risk factors for suicide (3,6), and related risks like intoxication, long-term dependence and self-harm (7,8). Understanding these risk factors can help reduce health inequalities and support people to live longer, healthier lives in Gateshead.

This report examines the scale and impact of alcohol, drug and suicide-related deaths in Gateshead. It highlights the importance of language in discussing these issues. While the term "Deaths of Despair" resonated with some of those with lived experience that we consulted, it evoked difficult and mixed emotions. However, "despair" seemed to reflect the experiences of our communities; therefore, we have chosen the term "Ripples of Despair" for this report.

Sadly, these deaths are just the tip of the iceberg. Alcohol contributes to over 60 health conditions (9), with Gateshead recording 5,326 alcohol-related hospital admissions in 2022-2023 - one of the highest rates nationally (10). During the same period, 1,260 people accessed specialist drug treatment services (11), and estimates suggest 1,716 Gateshead residents were affected by opiate and crack use (12). Gateshead also has higher-than-average rates of self-harm, with 150 hospital admissions for self-harm among 10-24 year olds in 2022-2023 (13,14). Health inequalities worsen these challenges, with some groups and communities in Gateshead more affected than others.

Behind these statistics are real people, lives, families and communities. This report seeks to share their voices, illustrate the scale of this issue in Gateshead, and explore both the challenges we face and the opportunities we have to make a difference.

The local picture; deaths by alcohol, drugs and suicide in Gateshead

The statistics surrounding alcohol, drugs and suicide paint a stark picture of loss in Gateshead.

Between 2003 and 2023, 307 lives were lost to suicide in Gateshead (15). To put the number of suicides over the last two decades into perspective, the figure is nearly three times the number of road traffic deaths in the same period (16).

In addition, 321 people in Gateshead died from drug-related causes (17), and 667 more from alcohol-specific conditions over the same time period (18).

It is important to note that alcohol-specific deaths only account for issues like liver disease, leaving out broader alcohol-related harm such as heart disease or cancers. The true toll of alcohol is likely far higher (19).

In more recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on alcohol-specific deaths. Nationally, the sharp rise in alcohol-specific deaths during the pandemic was linked to increased alcohol consumption, especially among those already drinking heavily (20). Shifts in drinking habits, like more regular drinking at home, have deeply rooted alcohol in daily life, increasing its harm (21).

Sadly, Gateshead has experienced rising numbers of deaths from alcohol, drugs and suicide. For alcohol-related deaths alone, there were 283 deaths from 2020 to 2022, equating to 52.8 deaths per 100,000 people (10). In comparison, the North East's rate was 49.7 and England's was 39.7 per 100,000 people (10).

Unfortunately, since 2012, Gateshead's suicide rate has risen, aligning with national trends. From 2021 to 2023, 50 people died by suicide in Gateshead, a rate of 9.5 per 100,000 persons over 10 years old, similar to the England rate of 10.7 and North East's rate of 13.8 (22).

Potential years of life lost

These deaths disproportionately affect younger and middle-aged people, cutting lives tragically short. The years of life lost (YLL) metric measures the years a person could have expected to live, had they not died prematurely, highlighting the societal and economic impact of preventable deaths linked to alcohol, drugs and suicide.

Between 2020 and 2022, suicide in Gateshead resulted in 569 years of life lost, equating to 39.2 years for every 10,000 people, significantly higher than the England average of 34.1 (23,24).

Life lost to alcohol is even higher. In 2022, Gateshead had a high rate of potential years of life lost to alcohol, with 2,078 years lost per 100,000 males and 489 years lost per 100,000 females (9). For potential working life lost due to alcohol (before the age of 65), Gateshead males had the highest rate in England at 1,033 potential working years lost per 100,000 males (9).

Data on years of life lost due to drug use in Gateshead is limited. However, given the high number of drug-related deaths and the similar age range of those affected as seen with suicide, the impact on years of life lost is likely comparable, if not greater.

Alcohol and drugs are leading risk factors for death among people under 50 in Gateshead, with these risks escalating over time. In 2021, drug use contributed to 19.7 deaths per 100,000 - a 339% increase since 1990 (4). Meanwhile, alcohol-related deaths rose to 13.2 per 100,000, a 57% increase since 1990 (4).

Gateshead is falling behind the rest of England in these areas. The numbers show a growing need for action.

Deaths in drug and alcohol treatment

When people are engaged in treatment, their risk of drug or alcohol related death is reduced.

However, being in treatment does not mitigate risk entirely, as there can be other factors that can contribute continuing drug and/or alcohol use, along with other health vulnerabilities.

People may still die prematurely, even when accessing treatment and support. Between 2019 and 2022, and 2021 and 2022, there were 58 deaths among those in drug treatment and 15 among those in alcohol treatment (25). These figures were higher than in the previous period of 2018 to 2019. While not all deaths in treatment are directly attributable to substance use, it is often a contributing factor to health inequalities and premature death.

Deaths while accessing mental health services

Almost a third of those who died by suicide after contact with drug and alcohol services had also engaged with mental health services in the previous year (26). High rates of self-harm were also common (26). highlighting the need for stronger collaboration between drug and alcohol services and mental health services to mitigate ongoing risk, even once treatment is completed.

Things that made my drinking worse were bad situations. I had no coping mechanism for them.

The vulnerabilities of those accessing mental health services also mirror these concerns. Most patients who die by suicide share overlapping vulnerabilities, such as a history of self-harm (63%), more than one mental health diagnosis (54%), living alone (48%), and substance using involving alcohol (47%) or drugs (38%) (27).

In 2021, the UK saw 74 suicides by people who were mental health in-patients, accounting for 4% of all patient suicides. 12% of all patient suicides were by people who had been discharged from mental health in-patient care within the previous three months, the highest risk being the first 1-2 weeks after discharge with the highest number of deaths overall occurring on day three post-discharge (27).

These figures underline the importance of tailored suicide prevention efforts within mental health care. The Suicide Prevention Strategy for England: 2023-2028 outlines key actions, such as follow-up support within 72 hours of discharge and co-designed solutions with those with lived experience, to reduce preventable deaths (28).

Every life lost in Gateshead presents a chance to do better, together. Deaths resulting from alcohol, drugs and suicide are critically high in our region and often interlinked, reflecting the multiple challenges and disadvantages faced by many in our communities.

These overlapping vulnerabilities require a joined-up preventative approach which not only tackles the root causes of harm but strengthens support for those at risk. Change is both urgent and possible - we cannot afford to let these trends continue to rise.

The importance of prevention

In Gateshead, a confidential Drug-Related Death (DRD) review is conducted after every suspected drug-related death to identify patterns and opportunities for intervention. This collaborative process involves both statutory and non-statutory partners, all working to reduce the devastating impact of drug-related deaths on families and communities. With new national guidance, like the Preventing Drug and Alcohol Deaths: Partnership Review Process (28), there is an opportunity to improve the DRD review process in Gateshead, allowing for shared learning to better prevent these tragedies.

While reviews of drug-related deaths provide valuable lessons, the rising numbers in our region show that earlier intervention is essential.

Alcohol and drug dependency rarely occur in isolation - they are both causes and consequences of multiple disadvantages and inequalities, leading to interlinked vulnerabilities. Addressing these challenges requires a focus not just on treatment but on prevention, tackling the root causes of substance use and supporting people long before they reach crisis point.

Case study - Speak Their Name memorial quilt

The 'Speak Their Name' memorial quilt was created by those in the North East bereaved by suicide, with over 200 people attending workshops across the region to craft 120 individual fabric squares.

Working as both a suicide prevention initiative as well as a tribute to lost loved ones, the quilt toured public spaces with the intention of promoting hope and healing.

The project has been led by Tracey Beadle from the charity Quinn's Retreat and Suzanne Howes. Both have lost children to suicide and are determined to make a difference by bringing hope to those feeling lost, in their children's names.

The building blocks of health and wellbeing

Our health and wellbeing is shaped by many factors, starting even before we are born. These factors include where we live, the quality of our housing, our friendships and family, experiences at school, access to good jobs, and whether we have enough money to meet our needs. Together, these are the building blocks of health.

When building blocks are missing or broken, they can have a damaging effect on our health. For example, a baby born in one of Gateshead's most deprived areas is expected to live nearly 12 years less than a baby born in one of the least deprived areas.

Differences in these building blocks lead to health inequalities, which are unfair differences in health outcomes between groups of people. Deaths from alcohol, drugs and suicide are marked by these inequalities, with the highest rates of harm and death concentrated in the most disadvantaged communities.

Understanding risk factors for alcohol, drugs and suicide

A large study looking across all local authorities in England identified the following risk factors linked with deaths by alcohol, drugs, and suicide (3):

*(routine task jobs which do not require any educational qualifications)

These risk factors are shaped by the circumstances in which people live - the building blocks of health. The model below draws on several studies to help illustrate how risk factors are influenced by a range of social, political, commercial and economic factors (29-32).

Social and political factors

The conditions in which we live, learn, work and age, are shaped by social, economic and political factors (33). Changes to these factors can significantly impact our health. For instance, suicide rates often rise during times of economic recession, as financial insecurity and job losses increase stress and feelings of hopelessness (30,34). Policies such as austerity measures, interest rate hikes and cuts to public services place additional pressure on those already facing socioeconomic disadvantage. Families struggling to make ends meet may face the risk of homelessness, food insecurity, and other challenges that contribute to mental distress. These stressful life events not only worsen mental health but also increase the risk of suicide (30,34).

Media landscape

While the online world can provide valuable resources for connection and support, it also poses significant risks. Social media can expose vulnerable individuals to harmful content, including material that glorifies self-harm or provides information about suicide methods (35,36). A recent study found that 83% of people had encountered self-harm or suicide content on social media without actively searching for it, with 75% first seeing this content at age 14 or younger (36).

Young people are particularly at risk, as they may be influenced by celebrities and influencers who normalise risky behaviours like substance use. This can harm mental health and increase the likelihood of suicidal thoughts or behaviours (37).

There has been emerging evidence of the link between the online environment and suicide across all age groups, with suicide-related internet use featuring in 8% of suicides by people accessing mental health services between 2011 and 2022 in the UK (38). This includes accessing information on suicide method, visiting pro-suicide websites and communicating suicidal intent online. These people were most often aged 25-44 years (42%) and aged 45-64 (33%) whilst 18% were under 25 (38).

There is growing awareness of the role the online world plays in self-harm and suicide (39). The Online Safety Act 2023 aims to create safer online spaces by making it illegal to promote or encourage serious self-harm (40). Additionally, organisations like Samaritans have created guidelines to promote responsible reporting of suicide in the media, aiming to reduce further harm (41,42).

Commercial factors

Our last report showed that health is shaped by commercial influences, such as the availability, price and marketing of products. Industries like alcohol and gambling often glamorise their products, normalising harmful behaviours and increasing risks, including addiction and suicide (36). These industries also work to undermine awareness of the harm they cause, often funding campaigns with mixed messages, like promoting "responsible use" while embedding their products as central to our social lives (29,30,43).

This influence deepens health inequalities. Gambling venues, for example, are disproportionately located in areas of deprivation, targeting vulnerable communities (44). Gambling-related harms include financial hardship, relationship breakdowns, mental health issues and a higher risk of substance use (45).

There is growing evidence of the relationship between gambling, self-harm, and suicide (45,46), as well as how gambling and substance use exacerbate each other (44,45,47-50).

The workplace is another commercial factor influencing health. Good jobs can provide financial security, build confidence and strengthen social ties, protecting mental health (33). In contrast, poor working conditions or insecure employment can harm wellbeing, increasing stress and anxiety (33).

Community factors

Where we live has a significant impact on our health. Disadvantaged urban environments with high levels of noise, crime, rubbish and limited green spaces can increase psychological distress and depression, both risk factors for drug-related deaths and suicide (51,52). There are links with suicidal behaviours being increased when experiencing poverty and deprivation at an individual level, along with living in a more deprived community (53).

Deaths to alcohol, drugs and suicide are not equally distributed across England. Like many health outcomes, there is a marked North-South divide as well as a Coastal-Inland divide (3). Between 2019 and 2021, the rate of deaths by alcohol, drugs, and suicide was highest in the Northeast (54.7 deaths per 100,000 people). The rate in Gateshead was 48.7 deaths per 100,000 people, significantly above the England rate of 33.5 per 100,000 population. The geographical inequalities are visualised in the map below.

Map of age-standardised mortality rate for deaths of despair across local authorities in England (2019-2021)(3).

The relationship between deaths by alcohol, drugs and suicide and factors such as living alone, living in an urban environment, being economically inactive, and unemployment are amplified in the North of England compared to other parts of England (3).

When looking at deaths due to alcohol, drugs and suicide in isolation, the geographical picture is very similar. The North East has the second highest rate of deaths by suicide of any region in England and Wales in 2023 (14.5 deaths per 100,000 people) (54,55).

The North East is the region with the highest rate of deaths due to drug use (10.9 deaths per 100,000 in 2023); this has been the case for the past eleven years (56).The alcohol-specific death rate is also highest in the North East (20.4 deaths per 100,000 in 2021), as it has been for the seven preceding years as well (57).

Social cohesion and fragmentation

Areas with high social deprivation and low community cohesion, such as places where people frequently move in and out, or many single-person households, are more likely to see higher rates of drug-related deaths and suicide (52). By contrast, strong social ties and support networks, often referred to as social capital, act as protective factors, reducing the risk of harm (34).

VCS case study - Edberts House

Established in 2009, Edberts House is an organisation working with over 4000 people across Gateshead.

Their four community houses offer individual support and group activities, including men's groups, refugee support group, training courses and children clubs. These have encouraged residents to have autonomy over decisions affecting their lives, as well as strong partnerships across the wider community, supporting residents' mental health in particular, and improving social connections, forming relationships with groups of people residents would not usually interact with. It has had strong positive outcomes since its inception, with those involved in one of their houses reporting life satisfaction on a par with the English national average, whilst outperforming scores for levels of trust, sense of belonging and levels of anxiety (58).

Their Community Linking Project offers social prescriptions to patients of 25 GP surgeries in Primary Care, addressing the wider determinants of health, such as housing, finances and loneliness. Their Health Equity project tackles health inequalities, including their children, young people and families team, who build trusting relationships, asking 'what matters to you?' and work with people to achieve their dreams. Knitting people together in peer support groups is a vital part of this approach - building connection and healthy interdependence. Innovative social prescribing work in secondary care is now being piloted, including their Palliative Care Link Worker, and Midwifery Social Prescribers. Evidence collected through the project has been analysed by Northumbria University, and has demonstrated that the interventions, advice and/or support provided by Edbert's House yielded a statistically significant improvement in emotional well-being.

Individual factors

The challenges individuals face are deeply shaped by their circumstances. Poverty, discrimination and abuse are just some of the structural issues that increase vulnerability. Life events like relationship breakdowns or homelessness can add to the risk of harm from alcohol, drugs and suicide. For those experiencing multiple disadvantages, these risks often overlap.

Children and young people: adversity, trauma and building resilience

The foundations for lifelong health and wellbeing are laid in early childhood. Positive experiences during this time are linked to better social and emotional development, stronger educational outcomes, and improved long-term health, including longer life expectancy (58,59). Conversely, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as trauma, abuse, neglect or challenging environments, can lead to poorer outcomes like mental health challenges, unemployment, substance use, and homelessness (60,61).

The impact of adversity

While ACEs do not guarantee negative outcomes, they significantly increase the risk, particularly for children who face multiple adversities or live in poverty (62,63). Research shows that 85% of people in contact with criminal justice, substance use, and homelessness services experienced childhood trauma (64). Children who have been exposed to four or more ACEs as particularly vulnerable to poor health outcomes across the life course (65). However, many children overcome adversity when they have access to protective factors like stable relationships, supportive caregivers, and safe environments (60,63).

The pressures of child poverty, the cost-of-living crisis, and the lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have increased these issues in the North, where child poverty rates exceed the national average (66).

For example, in Gateshead, the rate of alcohol-specific hospital admissions for under-18s is nearly double the England average, highlighting the urgency for action.

Care-experienced children and young people

Care-experienced individuals are those who have spent time in foster care or children's home, and they face significant health and social inequalities (67-69). The factors underpinning and exacerbating these inequalities are often rooted in trauma and adverse childhood experiences and linked closely with poverty, education, housing, and many other building blocks of health (70).

They are at higher risk of mental health challenges, substance use, and premature death, often from "unnatural causes" like suicide or drug-related deaths (67,68,71,72). Children in care, often due to the trauma of abuse or neglect, may experience greater levels of drug and alcohol harm compared to their peers and are over four times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers (73,74).

Building resilience

Resilience is the ability to adapt to stress and adversity, and it can protect children from long-term harm. Positive relationships with parents, caregivers, friends, teachers, and wider support networks are critical, as they provide the stability and support needed to develop coping skills and build self-esteem (64). Building resilience is not a quick fix. It requires sustained, long-term support and interventions (3). Resilience-building strategies include:

- Creating safe, trusting environments for children

- Providing opportunities to build self-esteem and a sense of control

- Strengthening family relationships and addressing household challenges

- Offering community-level support and services to address broader inequalities

Gateshead's Health and Wellbeing Strategy reflects this commitment, prioritising "giving every child the best start in life", with a focus on conception to age two as a critical period for intervention (75). The Early Help Strategy (2023-26) builds on this by expanding Family Hubs and programmes to support family stability and reduce risks before they become set in.

By addressing individual and community risk factors, Gateshead aims to create environments where all children can thrive, breaking cycles of adversity and promoting wellbeing for generations to come.

Case study - Trusting Hands Gateshead

Trusting Hands Gateshead (THG) is a multidisciplinary team of mental health practitioners, employed by the Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust (CNTW), THG works with Gateshead Children's Social Care services to deliver trauma-informed care.

The service name, 'Trusting Hands Gateshead: Strengthening connections through stories, safety, compassion and care', was developed with input from young people in Gateshead residential care homes, supported by Gateshead Young Ambassadors.

THG aims to:

- Understand and address the emotional and mental health needs of vulnerable young people

- Support families and systems around young people to promote stability and resilience

- Enable young people with complex needs to thrive

Demographics

Age

Deaths due to alcohol, drugs and suicide are most common in middle age. Between 2019 and 2021, the highest mortality rates were among 45-60-year-olds (3). While middle-aged adults have the higher number of deaths, young adults face a disproportionate risk: alcohol, drugs and suicide accounted for 41% of all deaths among 25-29-year-olds (3).

Generation X, who are those born in the 1960s and 1970s have continued to have high rates of deaths from drug poisonings and suicide for the past 30 years (76). This may be linked to opioid use and the increasing health effects of ageing (76,77), alongside experiences of risks such as financial instability, and unemployment (76). This evidences highlights the need for action to protect future generations when facing adversity.

Ethnicity

Suicide and alcohol-specific deaths are most common in White and Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups, with Indian males also experiencing elevated alcohol-related death rates (78,79)

Alcohol-specific deaths age-standardised mortality rate per 100,000 in England and Wales 2017-2019 (79)

| Ethnicity | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|

| White | 15.3 | 8.1 |

| Mixed/Multiple Ethnic Groups | 12.5 | 8.2 |

| Indian | 16 | 1.9 |

| Bangladeshi | 0 | 0 |

| Pakistani | 2.5 | 0 |

| Asain Other | 7.5 | 1.5 |

| Black African | 2.5 | 2.2 |

| Black Caribbean | 3.3 | 2.4 |

| Black Other | 6 | 2.7 |

| Other ethnic group | 4.8 | 0.9 |

The National Programme on Substance Use Mortality data from 1997 to 2023-2024, indicates that where ethnicity is known and recorded at death registration, the majority of deaths involving illicit substances are among those of white ethnicity at 96.1% (80).

However, ethnicity data is often incomplete, and 30% of drug-related death records lack this information (80). Barriers to care and targeted support for ethnic minority groups remain a significant concern.

Sex

Across all three causes, most deaths are among males. In 2022, across England and Wales, males accounted for three-quarters of suicides, two-thirds of all drug poisonings, and two-thirds of alcohol-specific deaths (28,29).

Women between the ages of 16 and 24 are almost three times as likely (26%) to experience a common mental health issue as males of the same age (9%), and women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with anxiety as men (82,83). However, women are more likely to seek support (84).

Men in the UK have reported lower levels of life satisfaction, happiness, and the feeling that what they do in life is worthwhile, than women, according to the national wellbeing survey 2016-17 (85). Men are also less likely to seek help, often using substances as coping mechanisms for poor mental health, exacerbated by gender norms that discourage vulnerability (84) (86).

LGBTQ+ community

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ+) people face significant health inequalities throughout their lives. (87) Discrimination (both within and outside of healthcare), unmet needs, barriers to accessing appropriate support and negative experiences when accessing support all contribute to worse health outcomes.

It is difficult to assess rates of deaths due to alcohol, drugs, and suicide for those who identify as LGBTQ+ in the UK as sexual orientation and gender identity are not recorded on death certificates. (88) However, research in this area suggests the LGBTQ+ population experience a higher risk of mental ill health, self-harm, and suicidal behaviour (88), in addition to higher levels of hazardous drinking and illicit drug use (89-91). Inequalities in access to healthcare exist for the LGBTQ+ population and these barriers to care impact people accessing the support they need (88,89).

Neurodivergence

Neurodiversity is a term used to describe the natural variations in the ways all our brains work (92-94). Neurodivergence includes Autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Tourette's Syndrome, Dyslexia, among other conditions. Research indicates that autistic people are more at risk of suicidal ideation and attempted suicide than the general population, and the number of autistic people dying by suicide is approximately 2-8 times higher than those who are not autistic (95).

Potential underlying factors, specific to autism, which may increase suicide risk include masking or hiding autistic traits to fit in, which is detrimental to mental health, repetitive thoughts which can lead to rumination and feeling trapped; and lack of appropriate support (95). Autistic people have been identified as a priority group in the national suicide prevention strategy (96).

ADHD is also linked to an increased risk of suicidal ideation and substance use due to co-occurring mental health challenges like anxiety and depression (97-105).

Pregnancy

Perinatal mental health issues impact over 1 in 4 pregnant women and new mothers (106) and suicide is the leading cause of death during the period from 6 weeks to 1 year postpartum, with an increased risk for women facing multiple adversities (107,108).

For women experiencing drug and or alcohol issues, there is an intense stigma around pregnancy, birth and postnatal. It can be difficult to access the support they need to manage their mental health whilst caring for themselves and their children. Some mothers face the additional trauma of their children being removed (107). Pregnant or postnatal women who are experiencing adversity and disadvantage often experience feeling judged, misunderstood, shame and guilt. This can subsequently exacerbate their struggles with substances and contribute to further deterioration in their mental health (107).

Health status

Conditions such as chronic pain and respiratory illnesses like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are common among those with substance use issues (109,110). Chronic pain doubles suicide risk and can lead to substance use as a coping mechanism, further complicating care (109,111). For example, approximately 50% of alcohol and drug use disorder patients are affected by chronic pain (109).

Mental health and self-harm

Around 1 in 4 suicides in England are people who are known to mental health services(96).Mental health conditions such as borderline personality disorder, anorexia nervosa, depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia increase suicide risk (112). Dual diagnosis is where substance use disorder and mental illness co-occur, this can present additional barriers to care, as services often focus on one issue rather than addressing both simultaneously (113,114).

Self-harm is "an intentional act of self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of the motivation or apparent purpose of the act and is an expression of emotional distress" (115) and is a major risk factor for suicide. In Gateshead, emergency hospital admissions for self-harm are significantly higher than the national average (14), particularly among young people aged 10-14 where it is double the rate in England (116), indicating a critical need for mental health support locally.

Socio-economic position

Poverty

Living in poverty impacts people, and their health, throughout their lives (58). It goes beyond a lack of money—it's the constant stress, scarcity of resources, and loss of control and dignity that take a toll on mental and physical health. Living with debt is particularly damaging, linked to adverse outcomes, including deaths due to alcohol, drugs, and suicide (58). This constant strain, known as economic adversity, forces people to focus on immediate survival, often leaving little capacity to plan for the future.

The graphs below show the link between deprivation and death by alcohol, drugs and suicide. The most deprived 10% of areas have markedly higher rates of deaths from alcohol, drugs, or suicide than the least deprived 10% of areas.

Alcohol-specific mortality in England in 2021(directly standardised rate per 100,000, County & UA deprivation deciles IMD 2019, 4/21 geography).

(117)

Those with lower socio-economic status suffer greater harm from alcohol, even though they tend to drink similar or lower amounts compared to wealthier groups - a phenomenon known as the "alcohol harm paradox". (118,119)

This highlights how other factors, such as access to healthcare and nutrition, may amplify the risks for populations experiencing deprivation.

Deaths from drug use in England in 2020-2022(Directly standardised rate - per 100,000, County & UA deprivation deciles, IMD 19, 4/23 geography)

(120)

For deaths by suicide, the County & UA deprivation deciles do not demonstrate the same trends, potentially due to lower numbers of deaths across large geographic areas masking inequalities. Suicide also occurs at higher levels in some rural areas, which are generally less deprived (52,121). However, there is a clear difference of rates by level of deprivation when looking at data for smaller local areas (LSOAs).

Suicide rate in England 2019-2021(persons 10+ years, directly standardised rate per 100,000, LSOA 11 deprivation deciles IMD 2019)

(22)

Insecure work, low wages, cost of living, inflation, insufficient benefit provision all contribute to an economic landscape where poverty and deprivation are unavoidable for many (58). Unfortunately, the reality is not as simple as finding a job and earning enough money to move out of poverty. We know that more people are working and remain in poverty (58,122).

Employment status

Unemployment is strongly linked to poor mental health and is a risk factor for harmful drinking, drug use, suicide, and homelessness (123-125). During times of economic recession, unemployment often leads to psychological distress, which increases substance use as a coping mechanism. During these times, providing psychological support for those who have lost their job and are vulnerable to drug use is essential (126).

The Dame Carol Black review highlighted employment is an essential part of recovery from substance use, for both financial stability and to offer something meaningful to do (127).

According to the World Health Organization, decent work can improve mental health, but also provides a sense of purpose, confidence, and routine. It builds social connections and supports recovery for those with mental health or substance use issues (128).

However, people with drug issues face significant barriers to employment, including stigma, receiving treatment whilst working, mental and physical health challenges, and lack of skills or training. Addressing these obstacles requires both individual support and broader societal changes (129). Rates of employment for people with severe mental illness are particularly lower than for any other group of health conditions, underscoring the need for tailored interventions (130).

Case study - Individual Placement Support (IPS)

Gateshead & South Tyneside's Individual Placement Support (IPS) initiative connects job seekers in recovery from addiction with meaningful employment opportunities. Embedded within local drug and alcohol services, IPS has helped over 100 individuals secure sustainable jobs.

Across the two local authorities, the team believes that everyone in our communities deserves a fair chance, so works hard to help people in recovery to find meaningful and sustained work. Employers are also a key part of supporting the initiative, and work with Gateshead & South Tyneside IPS to offer new roles and opportunities throughout the year.

Contextual factors

Stressful life events such as relationship breakdowns, chronic illness, or bereavement can increase susceptibility to substance use disorder and suicide. (131,132) Childhood maltreatment is also a significant risk factor for early substance use and long-term alcohol problems (131). While these factors do not guarantee harm, understanding them helps target resources and support where they are most needed.

Exposure to conflict, violence and war: asylum seekers and refugees

Inequalities experienced by refugee and asylum-seeking populations throughout their lives may contribute to factors increasing risk of harm by alcohol, drugs and suicide. While refugee and asylum-seeking communities are diverse groups, people that have been displaced are likely to have common experiences related to being on the move.

Factors during migration journeys may include issues such as poor living conditions and fears that come with being trafficked. They may feel a sense of shame, or guilt, at having to have fled their country of origin - perhaps leaving loved ones and their homeland behind. Their living standards may be drastically different from their home country, lacking basic services and often experiencing violence and detention (133).

Stigma may be felt by those with a refugee and migration background upon their arrival into their host country. This may be surrounding barriers to accessing healthcare and other services, poor living conditions, separation from support networks and family, uncertainty surrounding work permits and legal status, and in some cases, immigration detention (133). There are also challenges around adapting to change, potential unemployment, racism and exclusion, social isolation and possible deportation (133).

Poor mental health is common and may include symptoms of anxiety and depression, PTSD, suicidal ideation and/or attempts, along with substance use disorders (134). Substance use is often initiated or increased after experiencing trauma, to self-medicate and avoid difficult emotions (134). Women and unaccompanied minors are particularly vulnerable, facing risks such as exploitation and harassment, correlating with substance use (134).

Exposure to conflict, violence and war: veterans

Veterans experience higher rates of depression, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and alcohol misuse compared to civilians (135,136). PTSD in particular can co-occur with problematic alcohol use (135,136).

Services like the Armed Forces Outreach Service and Walking with the Wounded report that alcohol misuse is a factor in up to 60% of referrals (137).

While suicide rates among veterans are generally lower than the general population, young early service leavers are at higher risk (137,138).

Domestic abuse

Domestic abuse has severe physical and mental health consequences for victims and survivors. Those experiencing domestic abuse are more likely to have substance use needs and experience homelessness (139). Rates of domestic abuse in the North East are higher than England, and drug-related deaths, suicide, and domestic homicides are more common in women experiencing abuse (139).

In 2021, women in the North East of England were 1.7 times more likely to die early because of suicide, addiction, or murder by a partner or family member than in the rest of England and Wales (140).

Rates of domestic abuse related incidents and crimes have been increasing, and Gateshead has higher levels than England, with 38 incidents per 1000 people in 2022/2023 (141). Among victims and survivors in Gateshead, data shows also increasing additional needs, with mental health needs most common (139).

Tragically, suicide is increasingly recognised as a consequence of domestic abuse, with 93 of the 242 domestic abuse-related deaths in England and Wales in 2022/23 being suicides (142).

There is therefore a strong association between substance use and domestic abuse - as a risk factor for perpetration and victimisation of domestic abuse. Perpetrators of domestic homicide have been found to have high rates of alcohol and/or drug use (143-146).

Homelessness

In 2022-2023, over 1,600 households in Gateshead faced homelessness(147).Homelessness severely impacts mental and physical health, with many people experiencing substance use, mental health challenges, and trauma (148,149). Children in these households are also affected, with impacts on their education, mental health, and family stability (123).

The health inequalities and poor health outcomes faced by those experiencing homelessness are stark. For those who are sleeping rough, there are significant needs related to mental health, drugs and alcohol (148,149).

The root causes of homelessness, including poverty, lack of affordable housing, and unemployment, are intertwined with the risk factors for alcohol, drugs, and suicide (149). Addressing these systemic issues is critical to reducing harm and promoting recovery.

Experience of the criminal justice system

People in contact with the criminal justice system face significantly higher risks of suicide and drug-related deaths. Offenders in the community are approximately six times more at risk of suicide than the general population, and the risk of drug-related death amongst this population is 16 times higher (150). Female offenders are at even greater risk, with rates of suicide and drug-related deaths 11 and 33 times higher respectively than the general population.

Barriers to accessing appropriate support further exacerbate these inequalities. Addressing health disparities in this population can improve overall wellbeing and reduce reoffending rates (151).

System and service factors

Services play an important role in supporting those at risk of harm from alcohol, drugs and suicide. Recover-focused interventions that prioritise holistic joined-up care can help individuals rebuild protective factors like stable relationships, employment and housing. These services and interventions include:

Talking therapies

Talking therapies are psychological treatments for mental and emotional problems like stress, anxiety and depression. There are several different types of talking therapy, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

Gateshead Talking Therapies offers free and confidential NHS support for those aged 16 and over who are registered with a GP in Gateshead, providing treatment to help individuals cope and recover.

Crisis support

Gateshead have four Crisis Beds for adults in mental health crises, offering short-term support for up to four weeks as an alternative to hospital admission. Staffed 24/7, these beds address urgent needs while helping to prevent acute mental health admissions.

In 2025, Gateshead will launch a Safe Haven, operating daily from 3-11pm. This service will offer rapid, non-clinical support to individuals experiencing crises, reducing distress, providing a listening ear, and offering practical guidance.

Alcohol IBA

Alcohol Identification and Brief Advice (IBA) offers simple, effective advice to individuals drinking at risky levels, helping them reduce harm (152).

While commissioned within GP and pharmacy services in Gateshead, IBA is also delivered in settings like homeless services, ensuring those not registered with a GP can access support and referrals to specialist services.

Naloxone

Naloxone is a life-saving emergency antidote to opioid overdose, temporarily reversing its effects (153). It may reduce the number of opioid related deaths, which make up the largest proportion of drug related deaths (154).

In Gateshead, Naloxone is distributed through commissioned drug and alcohol services, participating pharmacies and as part of discharge plans for at-risk patients at the QE hospital.

Employment support / IPS

Individual Placement Support (IPS) supports people with severe mental health conditions or substance use issues by helping them find and retain meaningful employment (130). Embedded within Gateshead's drug, alcohol and mental health services, IPS connects individuals with roles that match their strengths and ambitions, contribution to recovery and social inclusion.

Specialist alcohol and drug treatment services

Gateshead offers specialist treatment and recovery services for both adults (Gateshead Recovery Partnership) and young people (Positive Futures).

These services improve public health, reduce harm and generate system-wide savings by preventing costly health, social care, and crime-related issues (155).

Specialist Alcohol and Drug Liaison Nurse

Gateshead's Specialist Alcohol and Drug Liaison Nurse works within the Psychiatric Liaison Team at the QE Hospital, providing assessments, interventions and continuity of care.

By connecting hospitalised patients with community services, the nurse ensures smooth transitions and ongoing support for recovery.

Crisis team

The Newcastle and Gateshead Crisis Team offers 24/7 mental health support for young people and adults in crisis. Comprising nurses, social workers, psychiatrists, and pharmacists, the team provides assessments and home-based treatment as an alternative to hospital admission.

Alcohol Care Team

The QE Hospital's Alcohol Care Team delivers specialist interventions, including medically assisted withdrawal and discharge planning. They work closely with community alcohol services to ensure patients receive ongoing care and support after leaving the hospital.

Stigma, shame and discrimination

Part of what got me into the hole was this stigma attached with what happened to me, the stigma then attached with my mental health as a result of what happened.

Stigma, shame and discrimination deeply affect people harmed by alcohol, drugs and suicide. They shape how individuals experience these struggles during their lives and how families, friends and communities grieve after a death. Unlike other illnesses, like cancer, addiction and mental health conditions are often misunderstood, with society sometimes viewing them as issues of personal choice or control. This unfair perception creates barriers to seeking help and reinforces feelings of shame.

A recent report (156) commissioned as part of the NHS Stigma Kills campaign identified stigma as:

- Discrimination - the behaviour that resulted from the prejudice from others

- Experienced stigma - the experience of being stigmatised by other people

- Social or public stigma - the negative attitudes and prejudice held by society

- Anticipated stigma - the feelings people had when they expected to be on the receiving end of bias from other people

- Self-stigma - the internalisation of stigma felt by individuals resulting from social stigma

- Perceived stigma - the perception of how a particular stigmatised group is treated by others

Stigma is also embedded in the language, narratives and media that surround us. Labels and negative descriptors dehumanise people and shape how society views them and how they view themselves (157). For example, describing addiction as a "lifestyle choice" or mental illness as an "excuse" creates damaging stereotypes that blame individuals for the struggles they face and ignore the systemic disadvantages and traumas that contribute to these conditions.

With 'commit suicide', we talk about people committing a crime, but something about committing suicide, to me, suggests that it is in the same ballpark. It sounds like a deliberate act.

Outdated language, like "commit suicide", reflects stigma rooted in the past where suicide was a crime in England and Wales until 1961. Although attitudes have shifted, stigma around suicide and mental health remains. Research shows that 1 in 5 people will have suicidal thoughts during their lifetime and 1 in 15 will attempt suicide (82), yet most won't disclose their feelings due to fear and worry about how others will respond (158).

My cousin took her own life as a result of heroin. Her family refused to use the words 'committed suicide'; instead, they would say she 'took her own life'.

Language matters. The words we use to describe addiction, mental health or suicide can either reduce stigma or deepen it. These judgements extend to healthcare settings, where stigmatising views can influence the care people receive (159). Stigma shaped by society may be internalised. People start seeing themselves through the lens of the prejudice they face, lowering their self-esteem (160) and pushing them further into addiction and/or despair (161).

The impact of stigma and shame

Stigma has real, harmful consequences. It stops people from seeking help, isolates them from support networks, and creates barriers to treatment. (162,163) For example, men are often discouraged from expressing emotions due to traditional ideals of masculinity, making them less likely to seek help for mental health or addiction (164,165) .

For women, stigma is often tied to societal expectations about their roles. A recent study found that women in recovery from alcohol dependence described shame as stemming from failing to meet stereotypes of being a "good mother" or "ideal woman". These expectations contributed to their use of alcohol as a way to cope (166).

Mental health is also stigmatised in many parts of the world, with different cultural concepts of mental health and internalised stigma reducing people's chances of seeking adequate healthcare even when available (167). In some communities, mental ill health is not spoken about. Refugees and asylum seekers in particular can face stigma, with many fearing seeking help due to cultural taboos, mistrust of healthcare systems, fear of authority, as well as a potential lack of familiarity with treatment for these conditions (165,168,169).

Reducing stigma

Reducing stigma starts with changing how we talk about these issues. Using compassionate, non judgemental language in all aspects of our life can make it easier for people to seek help and encourage society to see addiction and mental health struggles as health conditions, not burdens to face alone.

Case study: Recovery Connections Coffee Bike

It's a simple, powerful way to make recovery visible, share support options and challenge misconceptions and stigma around addiction.

At an event held at the Quayside last summer, the coffee bike sparked 220 conversations. By chatting with people who have lived experience, many attendees changed their views about addiction and learned that recovery is possible. The bike's success demonstrates how small acts of connection can reduce stigma, spread awareness and inspire hope.

The ripple effects felt by families, communities, and society

Families

When someone dies by suicide, drugs or alcohol, the impact on their family is profound. Beyond the devastating loss, families often face stigma, shame and isolation, making their grief even harder to bear. They may feel judged by others or experience self-blame, guilt and confusion.

This stigma often leads to reluctance in talking about the loss, and some families may even conceal the cause of death (170). This silence can intensify feelings of isolation and grief, highlighting the importance of access to support services and groups (171). Grieving these types of deaths is often described as 'traumatic grief' - a prolonged and intense form of loss marked by emotions such as guilt, anger and unanswered questions (172,173).

Studies have shown that people bereaved by suicide are twice as likely to be diagnosed with depression or anxiety themselves and are at greater risk of post-traumatic stress disorder, suicidal thoughts and prolonged grief (174-176). It is widely reported that bereavement from suicide can make a person more vulnerable to suicide themselves, but it can also have a protective effect in that experiencing the loss and pain of suicide makes them feel that suicide is not something they could ever do (177-179).

For all deaths due to drugs, alcohol or suicide, the whole family is impacted, and a continuing cycle of trauma is possible if the needs of people grieving go unmet. The impact can continue to be felt in the generations that follow.

Children in families affected by addiction or bereavement face additional risks. They are more likely to experience mental health issues like anxiety and depression, struggle in school, or develop their own substance problems. Addressing these challenges through postvention support is critical to breaking cycles of trauma and reducing long-term harm (180-182).

Communities

The ripple effects of suicide, drug and alcohol-related deaths extend far beyond immediate family and friends, often impacting entire communities. these deaths are far more reaching than originally thought, extending beyond family, friends, and contacts to include people with a perceived closeness or someone who identifies with them (176).

It had been reported for decades that six people are affected by one suicide, based on the average size of immediate family (183). More recent research takes into account those wider ripples felt through the community and estimates up to as many as 135 people are affected, including acquaintances, colleagues, and even those who had limited interactions with the person, such as a familiar face in the local coffee shop or a member of the emergency services responding to the incident (184).

Using this figure, we can estimate that over the past 20 years almost 41,500 people may have been affected by suicide in Gateshead, whilst in 2023 alone around 2,160 people were potentially impacted.

People who have a close relationship with the person who died, including family members, close friends and associates, are described as 'suicide-bereaved'.

The difference between 'short-term' and 'long-term' bereaved is the prolonged and debilitating impact of the death felt by the long-term bereaved (185).

This highlights just how indiscriminate suicide is, it can affect us all in many ways.

Society

Suicide contagion

The notion that one person's suicide can influence another's suicidal behaviour is based on the Social Learning Theory; that people learn behaviours by seeing them in others. Where they identify with the person displaying the behaviours and see it as having a desirable outcome, their likelihood of carrying out the same behaviour is increased (186).

This is known as 'suicide contagion', "whereby one or more than one person's suicide influences another person to engage in suicidal behaviour or increases their risk of suicide ideation and attempts" (187).

Contagion can happen when a person is 'exposed' to a suicide either through direct exposure, such as suicide by a peer or witnessing the tragedy, or indirect exposure, such as a suicide reported in the media or identifying with the person who died. Both are reported to increase suicidal behaviour in people who are already vulnerable to suicide, especially in adolescents and young adults (132).

The impact on staff and services

Frontline workers, including those in health, social care and emergency services, often face secondary trauma from exposure to these deaths (188). Staff may experience feelings of sadness, guilt or anger, leading to burnout, compassion fatigue, or even PTSD. The practice of trauma informed care has been used to increase knowledge and understanding of trauma-based behaviours and appropriate interventions to support those using services. It is also vital that trauma related responses in the workforce are also identified and appropriate support given to the staff (188).

Gateshead Recovery Partnership offers initiatives to support staff who experience the loss of someone they've worked with, including "loss of life" forums and access to counselling through the Employee Assistance Programme. These measures provide safe spaces for reflection and support.

Emergency responders also face significant challenges, with 1 in 4 reporting thoughts of suicide linked to work-related stress or poor mental health (189). Resources like Mind's Blue Light Together platform provide crucial mental health support for those in high-stress roles (190).

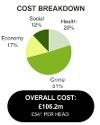

The economic impact

The cost of alcohol harm in Gateshead 2021/2022, can be broken down across four areas, economy, social, health and crime, with an overall cost of £106.3 million (191).

If we consider the cost of harm relating to alcohol from a healthcare and NHS perspective, alcohol related hospital admissions, outpatient visits, alcohol related A&E visits, alcohol related ambulance call outs, alcohol-related healthcare appointments and other alcohol related healthcare costs total £21.2 million (191).

Gateshead and the North East have high rates of alcohol mortality, which results in significant levels of working life lost. In addition, the ripple effect of alcohol harms more broadly, impacts the wider economy of Gateshead, at a cost of £17.6 million related to lost productivity at work, absence from work, and unemployment (191).

For drugs, Dame Carol Black's independent review exposed the scale of the national challenge. The financial cost from the harms of drug use to society is estimated to be £19.3 billion per year, 86% of which is attributable to health and crime related costs (192). Problematic drug use is highly correlated with poverty and impacting our most deprived communities (193).

The review identified the big business of illicit drugs, estimating its worth at £9.4 billion a year. As drug related deaths have risen, the illicit drugs market has become much more violent.

For suicide, the economic impacts range from financial losses due to years of life lost in employment, impact on employment and productivity for those bereaved, costs felt by the healthcare system, emergency services, coroners and families. The average cost of a suicide in the UK in 2022 was estimated at £1.46 million by the Samaritans, with overall suicides costing £9.58 billion (194).

However, when looking at Gateshead from 2018 to 2022, the total cost is estimated at £122 million, with the average cost per suicide slightly higher than the UK rate, at £1.5 million (194). This suggests that the economic impact of suicide in Gateshead may be greater than the national average.

These figures show that suicide prevention is a crucial area for public investment due to the significant emotional and financial cost caused by suicide each year.

Talking about death - death literacy

When I said, well, actually my dad took his own life, I started to feel sorry for the people that asked that question because I could see their Persona change instantly. I could see they felt bad for asking the question or shocked.

Death is a difficult topic to discuss, yet it's an inevitable part of life. This report highlights how death impacts those affected by alcohol, drugs and suicide, and how stigma can make grieving even harder for families. "Death literacy" refers to having the knowledge, skills and understanding to support others through dying, loss and bereavement. It's an important way for communities to offer compassion and care during life's most challenging moments.

Barriers to end-of-life care for people with alcohol and drug issues

People struggling with alcohol and drug disorders are less likely to access timely end-of-life care, missing the chance for a dignified and supported death (195). This group experiences what researchers call "structural vulnerability" - a lifetime of inequalities that follow them into death. Factors like poverty, trauma and stigma amplify this vulnerability, leaving their physical, emotional and social needs unmet (195,196).

Unlike predictable disease trajectories like advanced cancer, conditions caused by drugs and alcohol often involve a more uncertain decline, making it harder for healthcare professionals to plan or initiate conversations about dying. Unfortunately, avoiding these conversations leaves individuals without the opportunity to prepare for the future or express their wishes for care. Terminal illnesses tied to drugs and alcohol also carry additional stigma. As a result, people with drug and alcohol issues often don't receive palliative care until their final days - if at all - missing out on the comfort and dignity of a well-planned death and the accompanying care (195,197).

Fear can also play a role. Research shows that some individuals delay seeking care, worried they'll be judged, denied pain relief, or required to abstain from substances before receiving help (198). For those facing multiple disadvantages, like homelessness or hunger, addressing basic needs often takes priority over health, leading to late-stage care that's often too little, too late (199).

The current system often fails these individuals. Unlike integrated cancer or palliative care services, those with illnesses caused by drugs or alcohol experience fragmented and inconsistent support. They are frequently passed between services without receiving the holistic care they need, leaving gaps in treatment and bereavement support for their families.

The importance of 'end of life' literacy

Death literacy helps people plan for, navigate and support others through dying, loss and caregiving. It includes understanding practicalities like wills and healthcare preferences, as well as emotional and social aspects of death and grief. When this literacy is lacking, people can feel unprepared and isolated, while families and friends may struggle to cope with the loss.

When I spent time with Gateshead's addictions team, I heard how often they encountered death. While staff felt unprepared to talk about it, those with lived experience were much more open. Conversations about death seemed less of a taboo in this community.

Dr Elizabeth Woods, Consultant in Palliative Medicine

Improving death literacy can empower individuals and communities to offer better support during end-of-life care. Open conversations about death, dying and grief can break taboos and dismantle stigma, creating safe spaces for closure with compassion.

Compassionate cities: a model for better end-of-life care

Compassionate cites aim to create environments where aging, dying and grieving are seen as natural parts of life, supported by the entire community. This model integrates education, awareness and practical support into everyday spaces like schools, workplaces and homes (200). Grief is often thought of only as an emotional reaction to loss. However, this narrow understanding ignores wider social consequences of loss, including anxiety, depression, loneliness, social isolation, stigma, rejection, missed work or school, and even suicides and sudden deaths which can follow on from experiences of dying.

Compassionate cities aim to acknowledge these social impacts and promote health and wellbeing through better support, information and prevention initiatives which might mitigate these challenges.

Plymouth and Birmingham, the first compassionate cities in England, have taken steps to improve end-of-life care for marginalised groups, including those with drug and alcohol addictions. Initiatives like training "end-of-life ambassadors" and hosting workshops for street pastors and addiction nurses have enabled these communities to offer better care and understanding. By normalising conversations about death, compassionate cities help to dismantle the stigma surrounding dying, loss and addiction-related deaths. These efforts not only improve care for individuals but also build stronger, more empathetic communities.

Creating a compassionate gateshead

Gateshead has the opportunity to embrace the compassionate cities approach (201), ensuring that everyone (regardless of their circumstances) has access to dignified end-of-life care. For people with illnesses related to drugs and alcohol, early conversations about planning for the worst while hoping for the best could make a significant difference. By improving death literacy and addressing the inequalities that shape end-of-life experiences through our services, charities and communities, Gateshead can become a place where every resident can live - and die - with dignity, compassion and support.

Support following bereavement (post-vention)

Postvention refers to the support offered to individuals and communities after a death by suicide. Suicide has far-reaching ripple effects, often leaving those affected struggling with grief, mental health challenges and an increased risk of suicide themselves (202).

Yet many people in our communities do not seek the support they need, with one UK study finding that 25% of people bereaved by suicide received no support at all. Those who did often faced delays or lacked informal support compared to people grieving natural deaths (203).

Lack of support is a concern, as early intervention and effective support for those bereaved by suicide can act as important means of suicide prevention in a group who are at increased risk of poor mental health, suicidal thoughts and attempts, and dying by suicide. People bereaved may need the opportunity to access support services on more than one occasion at different stages of grief (204).

There is not a formal postvention support process in Gateshead for someone who has been bereaved by a drug or alcohol related death, but there are informal processes.

During Drug and Alcohol related death review meetings, for example, other individuals who may be at risk or affected by the death are identified, and the appropriate service reaches out to offer advice or support to help reduce further harm or deaths.

Specialist drug and alcohol treatment and recovery services in Gateshead can also offer support directly to family who contact the service following a death. If people accessing the service are affected by a death, the service will reach out and offer support and further harm reduction advice, such as trauma therapy and counselling.

While there is more structured support available within Gateshead from bereavement or mental health organisations in the area, it is not widely known about and may leave bereaved communities feeling unsure of where to turn to for support.

Embracing a compassionate place approach would support those experiencing loss unexpectedly from suicide, as the impact of grief and loss would be better understood by society and those impacted offered support by their wider communities, including the workplace.

Preventing harm and future deaths from alcohol, drugs and suicide

Good jobs, safe homes, strong communities and access to health and social support are the foundations of a healthy life. When these building blocks are missing or broken, people are more vulnerable to death and harm from alcohol, drugs and suicide. Efforts to prevent harm are often focused on specific individual interventions (30), like the system and services factors; however, addressing these issues requires co-ordinated action across multiple factors and sectors beyond healthcare.

Solutions addressing the social, political, economic, and commercial factors that impact health have the greatest potential impact, as they affect the whole population (30) and do not require high levels of individual agency or behaviour change. These approaches aim to reduce harm at the population level, before people reach crisis or become ill.

Gateshead's Health and Wellbeing Strategy provides an action framework across society, as a joined up, whole system approach; we call this the Population Intervention Triangle. The triangle focuses on three areas:

- Civic-level interventions: tackling social, political and economic factors like licensing laws and housing policies.

- Service-based interventions: offering high-quality care and support for those affected

- Community-centred interventions: engaging with people's lived experiences to co-design solutions

To reduce harm, Gateshead can act across these levels, strengthening the seams where these approaches meet, to create a cohesive, whole-system response.

While harm from alcohol, drugs and suicide can affect anyone, some groups are at much higher risk. Effective prevention requires targeted approaches tailored to specific risk factors, alongside universal strategies that address the entire population. The prevention pyramid is informed by a wide range of existing research, theory, and frameworks on prevention, and helps frame these efforts (205-212). Universal approaches target the entire population, such as campaigns to raise awareness about alcohol harm or mental health support. Targeted interventions focus on high-risk groups, such as young people, those in poverty, or individuals with mental health issues. Crisis responses and harm reduction provide immediate help for people already struggling, from suicide prevention to addiction treatment. Postvention supports those left behind after a death, aiming to prevent further harm.

By applying this model within Gateshead's civic, service and community efforts, we can take wide-ranging, co-ordinated actions to save lives.

Hopes for the future