Profit Before People: The commercial determinants of health and lessons from the tobacco epidemic (2023)

Foreword - Alice Wiseman, Gateshead Director of Public Health (including a PDF version)

It's hard to imagine how a seemingly innocent plant can by human action, become one of the deadliest products in history. Yet it happened in plain sight and has made huge profits for the industry that sells and promotes its consumption. If tobacco products came to market today, with the knowledge that they would go on to kill over half of regular users, I wonder what the reaction would be? Over centuries the tobacco industry was ruthless in its pursuit of financial profit from these dangerous products. They used a range of tactics which delayed policies aimed at protecting the health of the public regardless of the damage caused to Mams, dads, sisters, brothers, nanas, and grandads. It has taken over 60 years to reach the point where smoking is finally declining and the active deception, denial, and motives of the tobacco industry have been exposed. And yet cigarettes, and other tobacco products, are still freely available in our shops.

As the evidence of smoking harms became clearer, the tobacco industry framed smoking as an issue of individual freedoms and choices. Through a range of marketing campaigns and related activities, the industry continued to promote their products and target new markets and further normalising smoking. Public health advocates began to expose the truth about the burden of harms caused by smoking, and the complex range of factors that underpin it. In 1962 the Royal College of Physicians first outlined a comprehensive strategy to tackle smoking.

Few wished to hear that this product was responsible for significant levels of illness and death though, and a BBC report from the day it was published showed that smokers were not too concerned about the findings at the time.

Significant lobbying and misinformation from the tobacco industry meant it would be a further 36 years before we fully implemented this in the UK. Due to this delay many people experienced significant preventable harm and premature death.

In my first annual report as Director of Public Health for Gateshead I talked about the loss of my own father, aged only 54, from this lethal product. Most people I have spoken to over the past few years have their own personal story of loss in the hands of tobacco. The fact that the loss of all these loved ones were completely preventable makes it feel even worse.

This has driven on advocates of public health and instead of accepting that smoking was too hard to tackle, tobacco control approaches have been developed with multiple strands of work implemented in parallel and over the short, medium, and long term. And the results have been stunning:

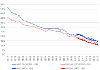

In 1998, 27% of adults in the UK were smoking when a national target to achieve a prevalence of 21% by 2010 was set . In the North-East region we have shown a steady rate of decline in smoking prevalence from 29.0% in 2005 to 13.1% in 2022. This represents a staggering reduction of 52.2% drop in actual smokers.

When people were better protected from industry influence, they did not choose to smoke. The vast majority of smokers wish they had never started, and I am yet to meet a smoker who doesn't want the next generation of children protected from taking up smoking. But we cannot relax in the face of a powerful industry. Recent research suggests that rate of smoking decline has dropped from 5% to 0.3%, likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, meaning fewer people quitting.

Our smokefree ambition for the North-East is to reach 5% prevalence by 2030 - but we want to go further. I want to see a North-East, and especially Gateshead, where no one experiences the harm and devastation caused by this lethal product. It might have taken over 60 years, but I think we can now confidently say that while the tobacco epidemic had a beginning, we've now progressed beyond the middle, and are today looking towards the end of tobacco. In October 2023 it was fantastic to see the Government commitment, following recommendations from the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Smoking and Health, and the Khan Review, to a smokefree future.

When I think about what we can learn from the tobacco control experience, I see many similarities with other harmful commodities. The pervasive nature of alcohol, ultra processed foods, and gambling in society (for example) have all the hallmarks of the tobacco industry playbook - profit and normalisation of the product take precedence over harm that is caused to people - your friends, families, and communities. People experiencing harm, illness and dying from entirely preventable causes. I see the same tactics - misinformation (underplaying the link between alcohol and cancer for example), challenging and delaying evidence based measures (the Scottish minimum unit price story), marketing of products and multi buy food offers (the majority of buy one get one free offers are consumed as additional calories rather than spreading the cost for those with low incomes (as the industry would have us believe) with additional profit going straight to industry shareholders) and the persistent unrelenting tactics used to lure people into gambling with a glimmer of hope on the back of substantial harm. Finally, industries suggest it's solely down to individual choice - people should responsibly gamble, drink, and eat, even though, and I am no business expert, I am pretty sure they wouldn't spend billions on marketing and promotions unless they were certain about increased profit.

As a public health expert with a statutory responsibility to protect and promote the health of the population, it can feel incredibly daunting. Policy continues to be influenced by companies whose explicit aim is to maximise shareholder profit. We haven't made anywhere near enough progress on protecting the population from other harmful products and industries, and much of the rhetoric on alcohol, gambling and ultra processed food is very similar to that of smoking back in 1962. However, I reflect on how daunted my public health predecessors must have felt in the early days of the fight for protection from tobacco and how grateful I am that they persevered with tenacity and passion. Their pioneering work and bravery have saved many lives and will save more in future generations. The public health voice must get louder in this space, people's health and well-being should come before profit. Public health policy needs to be protected from industry and, conflicts of interest in research and education need to be explicit and controlled.

I hope this report will help us to not only end the tobacco epidemic, but also to think about the other wicked issues that are doing so much damage to the health of the public in plain sight of everyone. This can feel overwhelming but as we've shown in this report there is hope. We have done it before with tobacco and we can do it again. We need people and communities to understand how they have been manipulated into thinking this is all about individual choice, but we can only do this by exposing how industries have literally wallpapered our lives with their version of the truth.

Introduction

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines a commercial determinant of health as 'a key social determinant referring to the conditions, actions and omissions by commercial actors that affect health'. (World Health Organisation (2021) Commercial determinants of health1.

The term 'commercial actors' means private sector businesses, and it is their commercial activities in providing goods or services for payment, and the circumstances in which that commerce takes place, that help shape the social and physical environments in which we live. While some activities may be positive (for example. creating jobs and so improving living standards), there are also negative impacts associated with the unrestricted pursuit of profit generation for shareholders. When it comes to making profits, the various multinational companies that make up the tobacco industry (TI) are past masters.

Such industries are commonly termed as unhealthy commodity industries, and this report will focus for the most part on the TI which is responsible for one of the biggest public health threats the world has ever faced.

All forms of tobacco use are harmful, and there is no safe level of exposure to tobacco. Cigarette smoking is the most common form of tobacco use worldwide, but we shouldn't overlook other tobacco products such as cigars, waterpipe tobacco, roll-your-own tobacco, pipe tobacco, cigarillos, bidis and kreteks, and smokeless tobacco products2.

Tobacco kills over eight million people a year around the world, with more than seven million of those deaths the result of direct tobacco use, while the remainder are the result of non-smokers being exposed to second-hand smoke.

There are 1.3 billion tobacco users worldwide, with around 80% of these living in low- and middle-income countries, where the burden of tobacco-related illness and death is heaviest. This international inequality is also reflected at smaller scale where less affluent communities have higher smoking prevalence and suffer greater harm than more affluent areas. Tobacco contributes to poverty by diverting household spending from basic needs such as food and shelter to maintaining the addiction.

The highest recorded level of smoking among men in Great Britain was 82% in 1948. By contrast, smoking prevalence among women in 1948 was 41% and remained constant until the early 1970s, peaking at 45% in the mid-1960s.

Overall, the proportion of adults (aged 16 and over) smoking in Great Britain has been declining since 1974 and current prevalence for men is 14.6% and for women 11.2%1.

This amazing decline is due to the persistent efforts of public health advocates who, despite the best efforts of tobacco manufacturers, have evolved a model of tobacco control over time which has seen smokers quitting and allowed the growth in the numbers of people who have never smoked. While some progress has been made in some western countries such as the UK, the TI continues to drive up their sales and profits in those countries less able to mount a coordinated response.

This report will examine how tobacco came to be the original commercial determinant of health, demonstrate that profit ultimately outweighs health and wellbeing considerations, how a Tobacco Control approach to reduce the harm caused by tobacco has (with great effort) made progress in the last few decades, and most importantly, what now needs to happen to create a smokefree generation and finally end the tobacco epidemic in our area. We will also consider the lessons learned from the Tobacco Control success story and what that may mean for some other key commercial determinants of health.

References

How tobacco became a commercial determinant of health (CDoH)

That a single apparently harmless plant can, through a series of human controlled steps, become one of the most profitable, yet immoral and deadly products ever known, is a story worth thinking about. That this happened in plain sight and without control or regulation for so long tells us a lot about the power of private enterprise, the harm this can cause, and what the public will tolerate.

Tobacco originated in South America and has been used for thousands of years by indigenous cultures for spiritual and cultural purposes. Early European colonists of the Americas noted the physiological effects of tobacco, whether smoked, chewed or inhaled as snuff and immediately set about commanding its growth and sale. Now a European commodity, profit became a priority, and, within a few years, tobacco was being grown in Africa, India, and the Far East, as well as in the American colonies.

However, as early as 1604, the health effects of tobacco were debated and King James I described its use as:

"loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, and dangerous to the lungs".

Yet these views did not stand in the way of profit, and by 1670, it is estimated that 50% of the male population of England were using tobacco for 'medicinal' purposes3. As a non-nutritional crop which provided large profits, tobacco displaced more beneficial crops and presented landowners with 'get rich quick' opportunities. As supply increased, prices fell and competition increased, making the labour and time intensive nature of growing and production less profitable. This had an impact on another evil but profitable trade - slavery. By the start of the eighteenth century, the mainly white tobacco growing and manufacturing workforce were replaced by slaves.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, various innovations such as sweeteners drove popularity further, particularly in the form of the cigarette, which while thought of as a lesser form of tobacco than the cigar, was cheaper, even if production was labour intensive. It took an hour to roll 200 cigarettes by hand, but with the introduction of a rolling machine, the output increased to around 200 cigarettes per minute. This period of industrialisation, innovation and aggressive empire building led some major tobacco producers to merge, forming the American Tobacco Company. This monopoly allowed competition, pricing, and profits to be controlled, and soon cheap cigarettes flooded western countries, increasing smoking prevalence with aggressive, targeted and very effective marketing practices developed to ensure a steady stream of new users.

Those with concerns about the health and 'moral' dangers of smoking soon found themselves outnumbered as the public turned to cigarette smoking, and the World Wars produced opportunities for the TI. The horrors of war put health concerns into perspective and soon cigarettes were being donated and distributed as part of support efforts on the home fronts. Soon governments were supplying this newfound 'comfort' to their servicemen, and cigarettes became a staple of military rations. This created a literal army of addicted smokers, each with their favoured 'brand.'

Meanwhile the TI continued using clever marketing and branding campaigns to compete for market share, while also conspiring to keep prices consistent, and the brand became a central attraction for smokers - Marlboro, Camel, Capstan, Embassy, and many, many more became household names all over the world. They all 'sold' an image, creating an identity for the smoker and a feeling of belonging to an exclusive club. By the end of the Second World War in 1945, cigarette smoking was universally accepted and promoted by ever more creative means that appealed to all - male and female, child, and adult. Iconic characters and brands were everywhere - on billboards and newspapers, in the hands of Hollywood A-list stars and cartoon characters - creating a society saturated by tobacco.

By the 1940s, enough people had been smoking for long enough that links between smoking and disease started to appear, and the TI started to take notice and prepare. Most notable was that cases of lung cancer had tripled in the previous three decades. However, the length of time between uptake of smoking and signs of disease made it difficult to prove a 'causal' relationship. Of course, this lack of 'proof' suited the TI, which recruited doctors into their advertisements to reassure smokers, launching efforts to dispute and deny evidence harmful to their profits.

Research continued of course, but there was always just enough room for uncertainty, a space into which the TI stepped enthusiastically to sow doubt and confusion. It was not until 1962 that a ground-breaking Royal College of Physicians report put the issue of tobacco harms beyond doubt. The TI response to this was telling - continued forceful and assuring marketing campaigns, while ignoring the accumulating evidence.

In 1963, the Philip Morris Tobacco Co. stated that: 'We believe there is no connection (between smoking and ill health) or we wouldn't be in the business'

Then came serious public relations exercises with the goal of producing and sustaining scepticism towards the scientific findings and creating controversy that would allow them to consistently suggest that the evidence was not strong enough. This in turn sowed doubt in the mind of the smoker (and non-smoker) creating a 'rationale' to continue, or to begin, smoking.

Doubt is our product, since it is the best means of competing with the 'body of fact' that exists in the mind of the general public - Brown and Williamson Tobacco Co. 1969

Political lobbying was another tactic, as was TI funded research which yielded favourable results, litigation against those who spoke out, and so-called 'scientific' breakthroughs such as low tar cigarettes and improved filters. In short, the TI, when faced with the horrifying truth, chose not to tell that truth or to save lives, but rather set out to maintain shareholders profits and to actively obscure and deny the damning truth.

It was not until the mid-1990s that leaked documents from Brown and Williamson Tobacco were published and the public became aware that for more than 30 years the company's public statements were completely different to their internal knowledge and activities - the cat was out of the bag. But as late as late as 1994, TI executives swore under oath in the US Congress that nicotine was not addictive. However, pressure continued to grow on them until in 1994, the State of Mississippi began litigation to seek financial damages for the harm caused. By 1998, 46 US States were involved, and the TI settled these claims to the tune of $206 billion. As part of the settlement agreement, thousands of pages of internal documents became available and laid bare the appalling record of activities that global corporations were willing to perform in the pursuit of profit.

References

3. Brandt, A.M. (2009). The Cigarette Century. Basic Books, Philadelphia

How do you control a problem like tobacco?

The negative impact of tobacco has been widely recognised and we won't go into great detail here. It is sufficient to say that tobacco is the single leading preventable cause of mortality, leading to 64,000 deaths in England each year and harming nearly every organ of the body. Up to two-thirds of smokers die due to their addiction, and it causes untold suffering, with those who start smoking as a young adult losing an average of 10 years of life expectancy4.

Estimates suggest there have been as many - if not more - deaths from smoking as from the COVID-19 pandemic. It is both a cause and a symptom of health inequalities in that it disproportionately affects those living in more deprived areas, causing and maintaining poverty through the cost of the product and is a solid commodity in organised crime.

Around eight million people have died in the UK due to smoking in the last 50 years, with an estimated two million more expected to die in the next 20 years without radical changes to smoking rates5 - the stark fact is that the TI have been responsible for 26% of all deaths that have occurred in that half century6. If it wasn't for the persistence of advocates for the control of tobacco, those figures would be much higher.

The toll of tobacco

Smoking deaths 1970 to 2019 in the UK

- 4.79 million men plus 2.95 million women equals 7.8 million total.

- 33% of all male deaths are due to tobacco

- 20% of all female deaths are due to tobacco

- 26% of all deaths are due to tobacco

Tobacco has been described as a wicked problem, the concept of which emerged to demonstrate that while some problems are 'tame' and can be addressed by simple direct problem-solving approaches, other problems are surrounded by disagreement, inadequate or conflicting information, large numbers of stakeholders and webs of interconnected interests - they are wicked because they are highly resistant to change7. Tobacco and smoking fall into this category because they are so deeply embedded into the fabric of society thanks to the unrestricted activities of the TI over so many years. Faced with wicked problems there is a temptation to assume that because there are no clear or simple solutions, they are simply too difficult to tackle. This often results in a focus on discreet elements of a problem with an assumption that this will be sufficient - but it rarely is.

Thankfully, many advocates for public health were unwilling to consider the problem too difficult to solve and in parts of the US, Australia and the UK, work was taking place that would establish the principles needed to deal with the problem. Tobacco Control (TC) evolved over time as a response to the excesses of the TI. It is shaped by an astonishing context: despite the importance of consumer protection in British society, products which are known to kill most of their life-long users are available for sale in shops throughout the land. As banning tobacco products is not an option, the very best that TC can do is to reduce the harm that tobacco inflicts on smokers, on smokers' children and families, and on society overall8. The principle of changing 'social norms' to create the social and legal environment where tobacco becomes less desirable, less acceptable, and less accessible was pioneered in California. Between 1988 and 1999, cigarette use in the US fell by 20%. In California, it fell by nearly 50%.

In 1999, the World Health Organisation (WHO) began work on the development of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)9 which was adopted by the World Health Assembly in May 2003 and came into force in February 2005. This was the first international treaty negotiated with the support of WHO and was developed in response to the globalisation of the tobacco epidemic. It is an evidence-based treaty that reaffirms the right of all people to the highest standard of health, represents a milestone for the promotion of public health, covers 90% of the world's population and has been ratified by the UK Government meaning they will abide by its legal obligations. Taking account of the history of TI actions, Article 5.3 of the FCTC states that: "In setting and implementing their public health policies with respect to tobacco control, parties shall act to protect these policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry in accordance with national law."

TC in the UK became viable in 1998, when the government published a white paper called Smoking Kills, which represented a milestone in public health. It provided a comprehensive strategy and identified funding that put the UK among the world leaders in TC. Over the following ten years, much of what the white paper set out to do was achieved. The high point of the work that was carried out was undoubtedly the implementation of Smokefree legislation in 2007, which literally changed the social and health landscape of the country.

In the North-East, the decision was taken in 2005 to create a comprehensive and coordinated regional TC programme called Fresh, which had the aim of driving down smoking prevalence. This programme operationalised the key strands of TC and linked them to local activity across the region. That smokefree legislation was approved in 2007 was in no small part due to the concerted action across the North-East, including Gateshead, and coordinated by the Fresh team. To control tobacco use, the following strands of action are required9 and should be implemented simultaneously, sustainably, and should complement each other:

- Monitor tobacco use

- Protect people from tobacco smoke

- Provide support to help smokers to quit

- Warn about the dangers of tobacco

- Enforce tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship bans

- Raise taxes on tobacco

Fresh has taken these strands and expanded them further and the implementation of this comprehensive evidence-based approach to controlling tobacco has resulted in reductions in smoking prevalence across the North-East. We continue to work collaboratively, both regionally and locally, to achieve a smokefree society.

The eight key strands of work Fresh have centred around:

- Building infrastructure, skills and capacity

- Advocacy for evidence based policy

- Reducing exposure to tobacco smoke

- Year round media, communications and education

- Supporting smokers to stop and stay stopped

- Raise price and reduce the illicit trade

- Tobacco and nicotine regulation

- Data, research and public opinion

This diagram shows some of the key points over the past two decades since Smoking Kills, illustrating the crucial role of advocacy in achieving policy change and how this correlates with smoking prevalence rates in young people:

As the harm of tobacco recedes, so the benefits of improved health and wellbeing increase. But progress is not easily won, and the effects of austerity, the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis in recent years has seen health inequalities widen, and progress in reducing the gap in life expectancy between the most affluent and the poorest in society has stalled. In this context, TC continues to represent a powerful tool in improving health in communities and is central to any strategy to tackle health inequalities as smoking accounts for approximately half of the difference in life expectancy between the lowest and highest income groups10.

The need to continue actively advocating and working on TC is ongoing and most clearly made when considering the tactics of a rich and organised adversary in the TI.

This has meant it has taken many years and much hard work to make progress on smoking as a commercial determinant of health:

| Year | Action |

| 1962 | Royal College of Physicians makes recommendations for reducing harm from tobacco in the "Smoking and Health" report. Its findings were supported by the US Surgeon General in 1964. Cigarette sales fell for the first time in 10 years and half of the UK's doctors had now stopped smoking. |

| 1971 / 72 | TI and government make voluntary agreement to include a health warning on cigarette packets and adverts. |

| 1974 | First national smoking survey shows that 46% of UK adults aged 16 plus smoke. |

| 1975 | As requested by government, TI agrees to cease advertising alongside U certificate films and stop advertising free samples. |

| 1978 | Radio adverts for cigarettes banned. Tyne and Wear County Transport agrees to make public transport smoke-free. (Adult smoking rate - 41% ) |

| 1984 | Smoking banned on all underground trains. (Adult smoking rate - 34.5%) |

| 1986 | Tobacco adverts banned in cinemas, some women's health magazines and Tyne and Wear Metro system. Selling any tobacco products to under 16s becomes illegal. (Adult smoking rate - 33%) |

| 1988 | USA court awards damages against a tobacco firm to the family of a smoker who died from lung cancer. (Adult smoking rate - 31.5%) |

| 1991 | Larger health warnings required by law on tobacco packaging. TV advertising for tobacco is now illegal in the EC. (Adult smoking rate - 29%) |

| 1992 | First nicotine patch available on prescription in the UK. (Adult smoking rate - 29%) |

| 1998 | Government produces "Smoking Kills" white paper with targets to reduce smoking prevalence. (Adult smoking rate - 28%) |

| 2002 | "Smoking Kills" warning covers 30% of cigarette pack. (Adult smoking rate - 26%) |

| 2003 | Tobacco ads banned from billboards, print media, direct and online advertising. (Adult smoking rate - 26%) |

| 2005 | Adult smoking rate - 24% Fresh, the UK's first and only regional tobacco control programme, set up in the North East. Tobacco companies banned from sponsoring global sports events. |

| 2007 | Smokefree public places goes live. Age of sale increased from 16 to 18 years old. (Adult smoking rate - 21%) |

| 2008 | Picture warnings on cigarette packets introduced. (Adult smoking rate - 21.5%) |

| 2010 | Annual tax escalator above inflation put on tobacco. (Adult smoking rate - 20.5%) |

| 2011 | Government sets targets to reduce adult smoking rate to 18.5% or less by the end of 2015. Cigarette machines banned. (Adult smoking rate - 20%) |

| 2012 | Point of sale displays banned in large stores. "Stoptober" annual quitting campaign launched. (Adult smoking rate - 20.5%) |

| 2015 | Point of sale displays banned in smaller retailers. Smoking banned in cars carrying children. (Adult smoking rate - 17.5%) |

| 2016 | Standardised packaging introduced. (Adult smoking rate - 15.8%) |

| 2017 | Government announce ambition to reduce adult smoking prevalence to 12% or less by 2022. Minimum Excise Tax put on cigarettes. (Adult smoking rate - 15.1%) |

| 2019 | "Track and Trace" system introduced to identify cigarettes being sold illegally. |

| 2020 | Menthol cigarettes banned. |

These achievements would not have been possible without comprehensive and continuous efforts from organisations and members of the public. Public health improvements do not happen by chance and when California reduced its efforts on tobacco control, smoking prevalence increased. These are important lessons not just for reducing the health harms of tobacco, but for other commercial determinants as well. The recently proposed age of sale legislation would be another step in the long journey towards a smokefree society. However, if action of this kind is recognised as important for tobacco, what will it take to see similar action on other commercial determinants of health?

References

4. Department of Health and Social Care (2023) Stopping the start: our new plan to create a smokefree generation GOV.UK - create a smokefree generation (opens new window)

5. Peto R and Pan H. UK deaths from smoking 1971 to 2019. University of Oxford. November 2021

6. Action on Smoking and Health (2021) ASH at 50 report (opens new window)

7. Johnston, J. and Gulliver, R. (2022) Public Interest Communications. University of Queensland UQ pressbooks - wicked problems (opens new window)

8. Action on Smoking and Health (2010) ASH - beyond smoking kills (opens new window)

9. WHO framework convention on tobacco control 2003 (opens new window)

Gateshead and smoking

Tobacco has had a lethal impact on the health of Gateshead over many years. The Director of Public Health annual report 2015 / 16, 'Tobacco: a smoking gun', detailed this and showed that the co-ordinated multi strand approach to tobacco control locally and regionally, had made good progress in reducing smoking rates. We know that smoking prevalence does not continue to decline without continued action - there were periods in the 1990s when reductions in smoking rates slowed and even stopped. Progress started with the introduction of local stop smoking services in the late 1990s supported by media campaigns promoting quitting, but by the mid 2000s this progress was beginning to stall. As mentioned, the Fresh (opens new window) comprehensive Tobacco Control approach was introduced in the North-East in 2005, with Gateshead as a part of this. At that time, 33% of adults in Gateshead continued to smoke12, including 17% of women who smoked throughout pregnancy, 39% of young people aged 11 to 15 had tried smoking at least once and 9% reported that they were regular smokers. Girls were more likely to smoke than boys with 10% being regular smokers compared with 7% of boys. A large majority of young people named shops, newsagents or tobacconists as one of their usual sources of cigarettes13, something that our Trading Standard teams were tasked to tackle and continue to support as part of Gateshead's multi strand approach of reducing smoking prevalence.

The Fresh programme took the evidence base around tobacco control and coordinated a consistent approach which further strengthened this evidence. Fresh supported the vision that efforts were best focused on raising motivation to quit and offering support for adult smokers, and in that way changing the world our children grow up in. Since that time major achievements include the introduction of Smokefree legislation in 2007, making it illegal to smoke in any pub, restaurant, workplace, and work vehicle anywhere in the UK.

This was a landmark moment for tobacco control and showed that efforts to improve health and wellbeing enjoyed overwhelming public support. In the year following the introduction of smokefree laws there was a 2.4% reduction in hospital admissions for heart attacks and a 12.3% reduction in hospital admissions for childhood asthma nationally14. By the time of the 2015/16 DPH report other measures were coming into effect - tobacco was no longer openly displayed and promoted in shops, smoking in cars with children present was banned, and plain packaging with picture warnings was introduced.

By 2016, smoking prevalence had reduced to 18.3% in Gateshead, with 20% of men and 17% of women continuing to smoke. However, 13.3% of pregnant women who gave birth in Gateshead were still recorded as smokers at the time of delivery15, which means more than one in eight babies were born to mothers who smoked. Each year 462 Gateshead residents died due to a smoking related disease and smoking was still the leading cause of preventable death16. The NHS costs related to smoking amounted to over £9.92 million in Gateshead17.

Although smoking prevalence continued to decrease between 2016 and 2021, it continued to disproportionately affect those on lower incomes who were more than twice as likely to smoke and less likely to quit18. This significantly contributes to health inequalities seen in our local populations

This clearly shows that while we have seen continued progress, health inequalities persist, and many areas of Gateshead still have significantly higher smoking prevalence rates than others, and this continues to impact life expectancy in our least affluent wards. The following graphic shows a short bus route in Gateshead and highlights the unacceptable difference in life expectancy for both males and females - just a few stops apart

Gateshead has seen smoking rates more than halved since 2005 - from the 33% of adults smoking to 14.1% of adults smoking in 202119. However, that is still 22,251 smokers and smoking related disease is still estimated to kill 337 people each year and account for 1,899 years of life lost annually20. Although reductions have been seen, we continue to see widening inequalities and the numbers of residents who quit from more at-risk populations, such as those with severe mental illness, are significantly lower. Smoking in pregnancy is still five times more common in the most deprived groups compared to the least. Latest figures show that in Gateshead, 11.8% of women smoked at time of delivery and 15,733 children live in households with adults who smoke which not only damages their health but increases their chance of becoming smokers 4-fold21. In Gateshead, 29.8% of those in routine and manual occupations smoke22, 3.5 times higher than for those in professional and managerial work.

Smoking rates are also much higher among people with a mental health condition. Links around housing tenure have also been identified, we now know that people living in social housing have smoking rates which are double the national average. In Gateshead 33.2% of people who rent from local authority or housing association smoke compared to 7.4% who own their home outright23. People living with social and economic hardship find stopping smoking far more difficult. Smoking is more common in the communities they live in, they tend to have started younger and have higher levels of dependency on tobacco, all of which make it harder to quit successfully.

We continue to see the burden smoking on our health and social care systems. Every year in Gateshead, smoking causes:

- 2707 hospital admissions

- 94940 GP appointments

- 52520 GP prescriptions for smoking related conditions

This results in annual healthcare costs for the NHS in Gateshead of £9.31 million, 15% of the overall cost of smoking for the borough16 . Current smokers are also 2.5 times more likely to require social care support at home and need care on average 10 years earlier than non-smokers, accounting for 8% of local authority spending on adult social care24.

So, progress has not been equal across our population. This demonstrates how important it is to deal with public health issues in a range of innovative ways, based on the best available evidence, and to do this in a comprehensive and consistent way over a long period of time. There is no single, simple intervention to these complex problems and no quick wins. It also shows us that the job is not done, and we need to keep moving forward together to end smoking once and for all, especially because we know that when efforts reduce smoking prevalence begins to rise.

These numbers, whilst stark, only tell part of the story. We must not overlook the huge personal costs of tobacco, not just for smokers but for their loved ones too.

References

12. General Household survey 2005

13. Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people. NHS Digital, 2017NHS digital - Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England (opens new window)

14. GOV.UK - impact of smokefree legislation evidence review March 2011 (opens new window)

15. GOV.UK - Local tobacco control profiles for England (opens new window) PHE, 2016

16. ASH Ready Reckoner (opens new window)

17. Smoking and poverty calculator. Action on Smoking and Health, 2016

18. ASH - health inequalities and smoking 2019 (opens new window)

19. Public Health Outcomes Framework - data OHID (opens new window)

20. Smoking Prevalence in adults (18+) Annual Population Survey (APS) 2021: Local Tobacco Control Profiles - Data - OHID GOV.UK HID - tobacco control data (opens new window)

21. DHSC press release for Better Health Campaign GOV.UK - Children whose parents smoke are 4 times as likely to take up smoking themselves (opens new window)

22. GOV.UK HID - tobacco control data (opens new window)

23. Annual Population Survey (APS) 2019: Smoking Prevalence in adults (18+)- Current Smokers by housing tenure. Local Tobacco Control Profiles - Data - PHE, GOV.UK HID - tobacco control data (opens new window)

24. (H Reed (2021), The costs of smoking to the social care system and related costs for older people in England: 2021 revision.ASH cost of smoking to the social care system March 2021 (opens new window)

Case study: The personal cost of smoking

"To tell your family you have cancer because of smoking and to see the shock and the worry on their faces is so hard. My daughters thought they were going to lose their mam."

Mum of three and sea swimmer Sue Mountain, 57, from South Shields, started smoking aged 11. She underwent laser treatment aged 48 after a biopsy revealed she had laryngeal cancer in 2012.

The cancer then returned in 2015 and then again in 2017 but she is now cancer free.

Sue said: "When I started senior school, you were the odd one out if you didn't smoke. You felt big and my school meal money went on cigarettes. At that age, you never think you're going to end up addicted or how smoking is going to ruin your life.

"When I was happy. I smoked. When I was stressed, I smoked. You lie to yourself and say you love smoking but you need the cigarette - that's the addiction. Over the years I think I probably spent over £100,000 on cigarettes... I could have bought half a house with that or seen the world instead of getting cancer.

"Around 2010, I noticed I always had a dry throat and that my voice disappeared in the summer. Initially, I put it down to the change in weather but it continued to happen and in 2012 my partner at the time told me to get it investigated.

"I honestly didn't think it was anything serious, so when I got diagnosed with early-stage laryngeal cancer I was devastated.

"To tell your family you have cancer because of smoking and to see the shock and the worry on their faces is so hard. My daughters thought they were going to lose their mam.

"I immediately gave up smoking and underwent laser treatment, which was successful and I was thrilled to be given the all-clear. Then, about a year and a half later, I started smoking again due to stress. I smoked on the sly, hiding it from my three daughters as I knew they would be really upset that I had started again. Unfortunately, they found out and I promised to stop, but I didn't."

In 2015, Sue's cancer returned.

Sue explains: "I had laser treatment and got the all-clear again, but I didn't stop smoking. It had taken control of me.

Then in early 2017, I noticed my voice was getting even worse. I went to see my consultant and was told cancer has returned again, but this time it was more aggressive.

"I finally managed to quit just before my radiotherapy started. I had five days of treatment for four weeks and it was tough. I couldn't eat, couldn't drink, I had a tube down my throat for three months. I was so weak all I could do was lie on the sofa. My voice has never been the same since radiotherapy. But I'm fortunate, I am alive and feeling fit and I never think of going back to a cigarette.

In 2023, Sue pleaded with the Government to do more to help end smoking and spoke at an All Party Parliamentary Group Smoking or Health event for the second time.

"Most smokers begin as kids, long before you really understand addiction, or the risks. But tobacco companies understand the risks all too well. Tobacco companies are profiting and they should be sued and that money paid used for treatment and prevention."

"Tobacco companies lied to people about low tars and they lured more women into smoking through glossy marketing and slims, which has resulted in more lung cancer and COPD, and people like myself who might have quit instead of getting cancer. They wanted us to keep smoking and those diseases are still being seen in our hospital wards today."

"Why do we tolerate this? Why aren't we doing more to stop people dying? It's time tobacco companies were made to pay for more support for smokers and awareness campaigns encouraging people to stop."

"It's shocking that tobacco companies are making massive profits from an addiction that robs people of their lives and their health. Everyone is having to make savings right now. I believe they need to pay for the damage they do and fund work to reduce smoking."

Sue's story was shared with Fresh as part of their Smoking Survivors campaign.

The end of smoking and a smokefree generation

What are the next steps in finally ending the tobacco epidemic and placing the harms caused by these products firmly into history?

The end of smoking

Public support to end smoking is greater than ever from both smokers and non-smokers alike. Surveys show that 69% of adult smokers in England want to quit and that 75% regret ever having started smoking, but it takes on average thirty attempts before a smoker successfully quits25. As of 2021, 26.5% of the population of Gateshead are estimated to be ex-smokers26.

We are fortunate to have the continued support of Fresh and our comprehensive approach has seen consistent rates of decline in smoking prevalence, but as we've seen above there is significant work still left to do. We have a shared vision regionally to reduce smoking prevalence to 5% by 2030 which is mirrored in the 2019 stated national governmental ambition27. Based on the current trajectory we will miss our target by over seven years28, even more in our most at-risk groups, and without continued focus and action, smoking will remain as a leading cause of health inequalities. In June 2021, The All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG), a crossparty group of Peers and MPs, published a report and twelve recommendations to secure the Government's ambition of a Smokefree country by 203029. A key ask of this report was an increase in funding, legislation to ensure tobacco manufacturers pay for a Smokefree 2030 Fund to bring an end to smoking, and a call for a consultation on raising the age of sale for 18 to 21. In June 2022, an independent review commissioned by the UK Government was conducted. Known as the Khan Review: Making Smoking Obsolete28, this report once again laid out a series of recommendations on how the Government's ambition to reduce the national smoking rate to less than 5% by 2030 can be achieved. Four critical recommendations are below:

- Urgently invest £125 million per year in a comprehensive smokefree 2030 programme. Options to fund this include a 'polluter pays' levy.

- Raise the age of sale of tobacco by one year, every year.

- Offer vaping as a substitute for smoking, alongside accurate information on the benefits of switching, including to healthcare professionals.

- The NHS needs to prioritise prevention with further action to stop people from smoking, providing support and treatment across all of its services, including primary care.

Khan concludes in his report that: "Taken together, and if implemented in full, I believe these actions will get the government to its 2030 target and then lead to a smokefree generation. It is this level of comprehensive approach which will allow us to change the smoking landscape and secure a smokefree society for future generations whilst targeting our most vulnerable target groups to support them to quit smoking and ensure we reach our target of 5% smoking prevalence by 2030".

Gateshead has officially endorsed the recommendations set out in both the APPG report on smoking and health and The Khan review. As a Council we continue to work towards our vision for a smokefree society, free from the burden of tobacco addiction and the devastating impact it has on our local populations and health and social care services. In October 2023, theDepartment of Health and Social Care (DHSC) published a policy paper called 'Stopping the start: our new plan to create a smokefree generation' (opens new window). In this, the government sets out an intention to create the first 'smokefree generation' through the introduction of a range of proposals.

These include:

- increasing the age of sale for tobacco year on year so that someone born in 2009 will never be able to legally buy tobacco

- funding for initiatives to improve smoking cessation support

- increased funding for LA led stop smoking services and the national vaping 'Swap to Stop' scheme

- proposals on the regulation of e-cigarettes.

Of these measures, the proposal to increase the age of sale has the potential to be very effective in cutting of the supply of new smokers to the TI. While these proposals are to be welcomed, they fall short of a national comprehensive TC plan. A consultation on these proposals ended on 6 December 2023 and further details are awaited.

E-cigarettes

E-cigarettes or vapes have generated media interest recently and so it makes sense to briefly set out the current evidence-based position at this point. While we can't say that vaping is risk-free, we do know that it is far less harmful than smoking tobacco. They have been available for more than a decade, have become the most popular way to quit smoking, and there is strong evidence that they are an effective quitting aid. This is confirmed by an ongoing research study30 which looks at the evidence in several areas related to vaping.

This found that in the short and medium term, vaping poses a small fraction of the risks of smoking, but vaping is not risk-free, particularly for people who have never smoked.

We know that vaping products remain the most common aid used by people to help them stop smoking and more people successfully quit when using vapes compared with traditional nicotine replacement therapy or behavioural support alone. Despite this, misunderstandings about potential harms persist and around a third of adults believe vaping is as harmful or more harmful than smoking. This is worrying, as it means that people who would benefit from using vapes to reduce and quit smoking, could be missing out whilst continuing to experience harms and damage to their health from tobacco smoke.

We need to be clear that for those who have never smoked, developing a nicotine addiction through vaping would not be in their best interests. Vapes are not risk free and we do not yet know the long-term effects of many vape ingredients31. Therefore, vapes shouldn't be made appealing, or marketed towards young people, and adults who do not smoke. Tobacco companies are involved in the e-cigarette and vaping market and have promoted and advertised these products in several ways including through social media, paid celebrities, and influencers32. These are proven TI marketing strategies which appeal to young people33.

There is also concern that this issue provides a route in for the TI to influence policy, where it was previously excluded as part of tobacco control. (University of Bath Tobacco tactics - e-cigarettes (opens new window)) The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control includes the need to prevent the TI from influencing health and tobacco control policy due to their vested commercial interests34.

Regarding young people, use of vapes was estimated to be 8.6% of 11 to 18 year olds in 2022, which is an increase on previous years30, but a recent study looking at 16 to 24 year olds found little evidence that vapes are a gateway to smoking, as smoking rates would be expected to change line with vaping rates over time35. In reality, youth smoking rates are at an all-time low with 88% of secondary school (11 to 15yrs) pupils having never tried smoking and 3% estimated to be current smokers in 202136. Most young people that have never smoked, haven't vaped, and it is important to remember that while some young people will try vaping as the likelihood of risk-taking behaviour increases with age, in the recent past that behaviour would likely have been smoking.

It's illegal to sell vapes to under 18s and proposals to strengthen regulations around e-cigarettes in the recent government announcement are broadly welcomed. In Gateshead, Trading Standards officers work on preventing and stopping underage sales of vapes and alcohol. In 2023, local officers identified vapes specifically targeted at children and seized large quantities of teddy bear shaped vapes.

In summary:

- Vapes pose a small fraction of the risk of smoking but are not completely risk-free.

- For those who smoke, switching to vaping could help them successfully quit.

- To protect their health, those who have never smoked shouldn't vape. These products shouldn't be marketed or promoted to children and young people, and those who don't smoke.

- Vapes are not intended to be used by children and it is illegal to sell them to under 18s

References

25. Chaiton, M. et al (2016). Estimating the number of quit attempts it takes to quit smoking successfully in a longitudinal cohort of smokers. BMJ attempts to quit smoking (opens new window)

26. Annual Population Survey (APS) 2019: Smoking Prevalence in adults (18+)- Current Smokers Local Tobacco Control Profiles - Data GOV.UK HID - tobacco control data (opens new window)

27. HM Government (2019). Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s - consultation document. GOV.UK - Advancing-our-health-prevention-in-the-2020s (opens new window)

28. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2022). The Khan Review: making smoking obsolete.GOV.UK Khan review making smoking obsolete (opens new window)

29. ASH - delivering a smoke free 2030 (opens new window)

30. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2022) Nicotine vaping in England: 2022 evidence update main findings.GOV.UK - HID vaping England 2022 evidence update (opens new window)

31. GOV.UK - Chief Medical Officer for England on vaping (opens new window)

32. University of Bath. Tobacco tactics - E-cigarettes. Tobacco tactics - e-cigarettes (opens new window)

34. FCTC - WHO (2013) Guidelines for implementation of Article 5.3. (opens new window)

35. Beard, E et al (2022) Association of quarterly prevalence of e-cigarette use with ever regular smoking among young adults in England: a time-series analysis between 2007 and 2018. Addiction, 117 (8), p 2283-2293. Wiley - e-cigarette use among young adults 2007 - 2018 (opens new window)

36. NHS - smoking drinking and drug use among young people in England 2021 (opens new window)

What lessons can we learn from the tobacco control approach?

There is no single answer to a complex problem like the tobacco epidemic. It is a wicked problem not amenable to short-term or simplistic/linear thinking. The complexity takes in multiple dimensions - the TI and their need for profit at any cost, the marketing that seeps into the public consciousness, the smokers (and non-smokers) that are affected, the health services treating conditions caused by smoking, the views of the media, the interest of the ruling politicians, and the list goes on.

Add to this the fact that all of these things apply at local, regional, national, and international levels and it is easy to think it is all too difficult. But through many years of working on tobacco we have proved that the TC model is an effective, appropriate and cost effective way to make significant progress.

We have proved that a comprehensive, multi-component programme applied consistently and over the long-term produces results. It is both vital to continue to tackle smoking so that we can end the tobacco epidemic for good, but also to learn from that experience to help tackle other complex public health issues.

The TC model provides a blueprint for planning how to reduce the harm caused by the other key commercial determinants of health.

Key lessons learned from the TC experience would suggest the need for the following steps/actions to be considered in relation to these other 'wicked' problems:

- Recognise the problem to be addressed and agree on the need to work together to tackle it, including the resource required to do so

- Develop and commit to a comprehensive, multi-strand and long-term collaborative approach

- Agree evidence-based and jointly owned objectives which are monitored and flexible enough to adapt to real time learning

- Work at scale and aim for consistency - some things only need doing once, but leave room for local flexibility

- One key message communicated by many voices

- Demonstrate visible and enthusiastic leadership at every opportunity

- Develop a communication strategy in support of efforts and ensure ongoing media presence

- Identify local champions, including political leaders and those impacted by the commercial determinants

- Develop awareness and support for change among the public and advocate on their behalf

- Focus primarily on adults - changing the adult world will change the environment kids grow up in

- Things don't happen quickly because culture change is complex - keep going, be tenacious and trust the approach

Other commercial determinants of health

When asked 'what makes us healthy,' often people think about the absence of a variety of illnesses, and the role that medicine, GPs and hospitals play in treatment. However, our health is not simply the absence of illness - it's so much more than that. Our health is strongly shaped by the conditions in which we are born, grow up, work, live and age. The key 'social, cultural, political, economic, commercial, and environmental factors' which shape our world are commonly known as the social determinants of health37. These issues do not work in isolation but overlap and work together to impact our lives. They also affect people in diverse ways due to factors such as 'age, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, and disability.'

'[Health is] not just the physical wellbeing of an individual but also the social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community, in which each individual is able to achieve their full potential as a human being, thereby bringing about the total wellbeing of their community.38'

Dahlgren and Whitehead produced a diagram to demonstrate the factors which influence our health and wellbeing and how they are related:

Within this broad range of issues is a key determinant which is generating much interest in recent times - the commercial determinants of health, which can be defined as:

'a key social determinant referring to the conditions, actions and omissions by commercial actors that affect health1.'

From a positive perspective, some commercial actors work to provide some essential products and resources. The World Health Organisation (WHO) notes that commercial activities are capable of shaping both the physical and social environments in which we are born, grow, work, live and grow old, which can be positive and negative in terms of influence:

'the private sector influences the social, physical and cultural environments through business actions and societal engagements; for example, supply chains, labour conditions, product design and packaging, research funding, lobbying, preference shaping and others1.

However, a recent paper published by the Lancet39 acknowledges that:

'the products and practices of some commercial actors - notably the largest transnational corporations - are responsible for escalating rates of avoidable levels of ill health, planetary damage and health inequity.'

This paper also highlights that a number of small industries, known as unhealthy commodity industries, are the driving force behind multiple health conditions, the rising burden of non-communicable disease, as well as our climate emergency. Four key industry sectors - alcohol, tobacco, ultra-processed food and fossil fuels, in addition to the climate emergency and non-communicable disease epidemic, are responsible for at least a third of global deaths.

As the influence of these transnational corporations continues to increase, and hence the harms to both individuals and climate health, so does their wealth and power39. However, those trying to counteract these harms become 'impoverished and disempowered or captured by commercial interest', and this 'power imbalance' and associated 'policy inertia,' results in health harms which our systems struggle to cope with.

Like tobacco, other commercial products which have a negative impact and are difficult to address include ultra-processed foods, sugary drinks and alcohol. We could also include problems caused by the gambling industry in this. In the North-East, this was recognised with the formation of Balance, which is a regional response to the health harms caused by alcohol and is based on the Fresh TC programme. Responses to other commercial determinants can also be informed by lessons learned from TC.

The TI had a playbook, a script, that emphasised personal responsibility for actions and impacts, paid for research and scientists to create doubt about legitimate scientific and public health concerns, carried out lobbying activities, and denied, and continued to deny for decades. These activities have cost millions of lives, and it is important to recognise the similarities with other corporate interests.

If we take the issue of food for instance, it is obviously different from tobacco, and the food industry differs from the TI in important ways, but there are also significant similarities in their responses to concern that their products cause harm. Obesity is now a major global problem, and we can't afford to repeat the mistakes of the tobacco epidemic, in which industry talks about the moral high ground but does not occupy it40.

The problem of overweight and obesity provides a useful example of how these factors overlap:

- Production and marketing of high fat, high salt, high sugar convenience foods

- Promotions such as 'buy one, get one free' in supermarkets and takeaways

- Jobs and workplaces which make it difficult for people to be active

- Workplaces with poor access to healthy food, or indeed supplying unhealthy food (vending machines)

- Lack of access to parks and green spaces

- Higher prices of unprocessed (healthier) foods

- Poor walking routes/cycle lanes

This is a small snapshot of the many factors which contribute to obesity, but already we can see how diverse they are and that they result in multiple problems that cannot be resolved easily, much as we found in considering tobacco harm. One common link between different commercial actors whose products cause harm are financial considerations - how much something costs to produce, how much to buy, healthy options (both food related or environment/infrastructure) being more expensive and complicated, and what profits can be made.

References

1. World Health Organisation (2021) Commercial determinants of health.WHO - commercial determinants of health (opens new window)

37. Lovell, N and Bibby, J (2018) The Health Foundation - 'What makes us healthy? An introduction to the social determinants of health' (opens new window)

38. Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales. Definition of Aboriginal Health. Cited in: Lovell, N and Bibby, J 'What makes us healthy? An introduction to the social determinants of health' The Health Foundation. (2018)

40. Brownell, K and Warner, K. (2009)The Perils of Ignoring History: Big Tobacco Played Dirty and Millions Died. How Similar is Big Food? Millbank Quarterly, Vol 8 (opens new window)

Alcohol

The scale of alcohol related harm

Harms arising from alcohol use are well documented, with over 200 diseases and conditions connected in some way to alcohol41. These harms are not just experienced by the person who drinks. Alcohol also impacts others in a negative way, including children and our wider communities. Alcohol-related harm is estimated to cost our society between £21 to £52 billion per year, and disproportionately impacts our more deprived communities. This inequality42 can be seen in our numbers for alcohol related death and disease. For example:

- In 2020, one in three of all alcohol specific deaths occurred in the most deprived 20% of the population, widening health inequalities42.

- In 2021, there were 20,970 alcohol-related deaths in England, which is a rate of 38.5 per 100,000 people. The mortality rate was highest in the North-East region 43

- The potential years of life lost (PYLL) due to alcohol-related conditions in the North-East remains significantly higher than the England rate. Nationally this equates to 293,979 potential years of male life lost, and in Gateshead this equates to 1333 years. For women the PYLL is lower than for men with a count of 138,058 nationally, and 592 for Gateshead, although the numbers show an increase on previous counts43.

- Whilst the North-East rate of admission episodes for under 18s for alcohol-specific conditions has come down over the last 20 years, it remains significantly higher than the England average. The rate per 100,000 for England is 626 per 100,000, compared with a North-East rate of 991 per 100,000, and a Gateshead rate of 1106 per 100,00043.

The alcohol industry relies enormously on high-risk drinking to increase its revenue44. The heaviest drinkers contribute the most to industry profits, therefore if the alcohol industry is in any way involved in influencing alcohol policy, there may be a significant conflict of interest as they have a vested interest in people drinking at higher levels. The price of alcohol is directly linked to alcohol harm. Evidence tells us that heavier drinkers tend to consume products that are cheaper and stronger on average45. Tax design in the alcohol market). Alcohol taxation and pricing policies, such as minimum unit pricing (MUP), are some of the most effective and cost-effective measures to reduce alcohol harms46. Whilst the other home nations have introduced MUP, we haven't in England, despite the emerging evidence of reduction in harm from Scotland.

The alcohol industry uses tactics to influence the social norms around alcohol. This is seen within prolific marketing across all types of media, often with links to charity campaigns and sporting events, even though alcohol has a detrimental effect on health and performance. More subtle forms of influence are seen with product placement within television and film, merchandise such as greeting cards or mugs with alcohol related slogans, and 'nudges' which influence people in their consumer habits47. Marketing of no and low alcohol products is another vehicle through which alcohol industry can influence us. The branding for these products is often almost identical to the products that contain alcohol. Whilst we have seen significant measures introduced to protect people from the influence from the TI, alcohol remains visible in our society to the point where it has become like wallpaper, and people no longer notice how it permeates through our society, influencing social norms. There is a lack of measures to address this despite the evidence of the harm alcohol causes, including the links to seven types of cancer.

The current self-regulatory system governing alcohol marketing does not work - despite existing codes prohibiting the targeting of alcohol adverts to children, more than 80% see alcohol marketing monthly, most are aware of various alcohol brands, and children as young as nine can accurately describe alcohol brands' logos and colours46.

The way alcohol is marketed normalises alcohol consumption and exposes children and vulnerable people to alcohol products, leading people to drink more and at an earlier age.

By funding youth education programmes, the alcohol industry has been shown to deliver content to children and young people that normalises moderate consumption of alcohol and downplays the health risks. A review of alcohol industry funded school-based education also showed the programmes served industry interests by focussing on people having personal responsibility for their alcohol use and that alcohol harm stemmed from people making 'poor choices' rather than focusing on the environment in which people are expected to make those choices48.

Children and young people, and people from lower socio-economic groups are priority groups to protect from the tactics of the alcohol industry. It is not okay for people to be exposed to an environment fuelled by the alcohol industry for their own gain, then to be blamed when their alcohol use becomes problematic.

References

41. WHO - alcohol (opens new window)

42. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2023) GOV.UK alcohol profiles for England March 2023 update (opens new window)

43. 50.4 per 100,000 population), and in Gateshead was 44.8 per 100,000 population. (Local Alcohol Profiles for England - Data - OHID OHID local alcohol profiles England (opens new window)

44. Bhattacharya, A. et al. (2018) Wiley - how dependent is the alcohol industry on heavy drinking in England (opens new window)

45. SSRN - Tax Design in the Alcohol Market (opens new window)

46. World Health Organization (2018). SAFER: Raise prices on alcohol through excise taxes and pricing policies.WHO pricing policies (opens new window)

47. Pettigrew, M. et al (2020). Wiley - Dark Nudges and Sludge in Big Alcohol: Behavioural Economics, Cognitive Biases, and Alcohol Industry Corporate Social Responsibility (opens new window)

48. van Schalkwyk, M. et al (2022) Distilling the curriculum: An analysis of alcohol industry-funded school-based youth education programmes (opens new window)

Case study: The personal cost of alcohol

Karen Slater, 55, is a Newcastle mum of four. She experienced alcohol harm firsthand when she grew up around alcohol in a hostile and dangerous environment. She was a victim of child abuse and domestic violence and sought solace in alcohol, drugs and self-harm. Karen recalls living in a deprived area, feeling isolated and alone, and believing that alcohol was the solution.

Karen said: "I already feel bombarded by the adverts of alcohol that come into my home and give out the message that alcohol is pleasurable and that it brings families together for the Christmas festivities. You can't move around a supermarket for piles and piles of alcohol.

"But alcohol advertising is insidious. It comes on the TV and looks really glamorous with the pink drinks - but it is a drug that is addictive. There are millions of people trying to battle alcohol and yet we are watching it on TV. Every night there are adverts, and as soon as you've seen that advert you think about it. For someone having a bad day or a bad moment that could trigger a relapse."

She added: "My reality and thousands of others is the exact opposite. If you've experienced alcohol problems, Christmas in the real world away from the alluring adverts of alcohol can be one of drink fuelled isolation, domestic violence, child neglect and A&E being overrun by drunken people.

"People who are alcohol dependent live lives constantly like this. The adverts never show that struggle and I feel they shouldn't be allowed to come into my home when I've never gave permission. My home is my haven. I'm in recovery. "

Karen shared her story with Balance as part of a media campaign for better regulation of alcohol advertising.

Ultra processed food and drink

The environment around us influences the choices we make on a day-to-day basis and our environment is 'obesogenic' - one where less healthy choices are the default and encourage excess weight gain and obesity.

In the UK, one in five children aged 10 to 11 years live with obesity. Children and young people are more likely to continue living with obesity into adulthood and to develop obesity-related chronic health conditions at a younger age. Data from the National Child Measurement (NCMP) programme49, shows that the prevalence of obesity for children in the most deprived areas continues to be more than double that of those in the least deprived areas. This link to deprivation is further highlighted, in most recent NCMP data (2022-23), with the North-East region having the highest prevalence rates of children living with obesity nationally in Year six and reception. In Gateshead, the picture is not improving, with 12.3% of reception and 27.5% of our year six children living with obesity. For adults, the outlook is similar with 68.4%50 reported as living with obesity and similar in terms of deprivation.

We know that tackling the harmful impact of ultra processed food and drink is complex and there are numerous factors that affect and impact our behaviour. There is a need to move beyond individual blame, recognise the tactics at play and seek a more comprehensive approach to the issue that increases opportunities for healthy and sustainable living both now and for current and future generations.

We have seen increasing attention on the role of commercial determinants of health on obesity51. This includes the marketing of less healthy foods such as those high in fat, salt, and sugar (HFSS). Research has shown that this is particularly influential on children and adolescents, with an impact on awareness, attitudes, and consumption, while driving up calorie consumption52 53. There is now emerging evidence that adults too are influenced by food advertisements in our local areas54. Advertising significantly contributes to normalising unhealthy foods in society and we are often unaware of how advertising affect decision-making and the industry's influence on our freedom of choice55 56.

It is interesting to note that a staggering third (33%) of food and soft drink advertising spend goes towards confectionery, snacks, desserts and soft drinks compared to just 1% for fruit and vegetables57. Existing regulations meant to protect children from junk food advertising were introduced for TV in 2007 and the non-broadcast environment in 2017. There are however significant loopholes in these regulations. Firstly, they only restrict junk food adverts when a TV show, film or website is designed specifically for children or considered to be 'of particular appeal' to them. They do not cover the times when children are most likely to be watching their favourite shows for example, between 6 and 9pm - often classed as 'family viewing'58.

Secondly, the existing rules to do not cover the vast range of channels and outlets through which children consume media in 2019. Children's media time often includes watching TV, going online using a mobile phone and playing games on gaming devices. The Obesity Health Alliance (OHA) wants to see a 9pm watershed on junk food adverts implemented across all 'media devices and channels not just on TV to protect children from the harmful effects of marketing of foods high in fat, sugar and salt'.

From a recent survey, there appears to be clear support among the UK public for these far-reaching restrictions in junk food adverts59. The UK does not have any rules for outdoor advertising spaces like billboards, bus shelters and digital displays. These and other outdoor public spaces are thought to be seen by 98% of the UK population at least once a week60.

The UK Government acknowledged the harmful influence of advertising on health in their 2020 Obesity Strategy, and then passed legislation to restrict advertising of food (HFSS) and drink online and on TV before 9pm. However, these policies have since been delayed until October 2025.

Areas of good practice include:

- The Transport for London (TfL) network showed that advertising restrictions successfully reduced calorie consumption (a 1,000 calorie decrease per week per household from unhealthy foods and drinks)61. Going forward it is hoped that these measures can potentially be effective through influencing individual choices but also pushing companies to expand to more healthier choices.

- Seven local authority areas in England have tried to restrict the advertising of products (HFSS) on council owned spaces, as part of wider strategies to reduce obesity.

References

49. GOV.UK - obesity profile update July 2022 (opens new window)

50. GOV.UK - obesity profile update July 2022 (opens new window)

51. The Health Foundation - risk factors for ill health (opens new window)

52. Kelly B, et al (2015) A hierarchy of unhealthy food promotion effects: identifying methodological approaches and knowledge gaps (opens new window)

54. Harris, J, Bargh, J & Brownell, K (2009) Priming effects of television food advertising on eating behaviour. Health Psychol; 28, 404-413 (opens new window)

55. Nanchahal, K., Vasilejevic, M., Petticrew, M., et al., 2021.A content analysis of the aims, strategies, and effects of food and non-alcoholic drink advertising based on advertising industry case studies (opens new window)

56. GOV.UK - advert restrictions re fat salt sugar (opens new window)

57. Food Foundation - The Broken Plate (opens new window) - The State of the Nation's Food System

58. OFCOM - children and parents media use and attitudes report 2019 (opens new window) OFCOM - children and parents media use and attitudes report 2018 (opens new window)

59. OHA - 9pm watershed (opens new window)

60. Ireland, R. et al (2019) NCBI Commercial determinants of health: advertising of alcohol and unhealthy foods during sporting events (opens new window)

Gambling

Gambling involves staking or risking something of value on an event with an uncertain or chance outcome. It's defined as gaming, betting, or participating in a lottery62.

There is increasing concern in the UK about the harms associated with gambling, where the gambling market is one of the largest and most accessible in the world63.

Statistics report there were almost 2500 gambling operators in the market in 202264, with earnings of £14.1bn in the year to March 202264. An estimated 60% of online gambling industry profits come from roughly 5% of gamblers who are classified as experiencing "problem gambling" or as "at risk"65

Over the last few years, there has been an increase in the availability of gambling, both in-person and online. Whilst there are some regulations of gambling advertisements, children are regularly exposed to gambling advertisements which can normalise and predict future gambling. Opportunities to gamble exist on most high streets and, with the spread of the internet, in virtually every home. Based on existing evidence, it is reasonable to say that the commercial gambling industry has become one of the most innovative health harming industries of recent times66.

It is no surprise to learn that the commercial gambling industry operates from a similar playbook to other health-harming industries, such as tobacco. This involves delaying and circumventing regulation, developing innovative products and promotions, appealing to new markets, co-opting the production of research and knowledge and capturing 'public health' responses through corporate political activities67.

There is ample evidence to show the significant negative health and social consequences of gambling not only for individuals who gamble, but also for families and communities66. The harm from gambling is a public health issue because it is associated with harms to individuals, their families, close associates and wider society and can both create and exacerbate inequities63.

It can be argued that the Gambling Act 2005 was harmful from its inception as it was designed to make the UK the centre of the online gambling industry, and defined people, not products, as the problem, while requiring regulators and local authorities to "aim to permit" gambling68. To date, Britain has taken the approach of working alongside industry, encouraging them to adopt 'responsible' corporate practice, rather than introducing legislation to regulate them.

It's important to remember though that gambling is sustained and promoted by a powerful global industry in ways that not only make it more widespread but also shape how we think about appropriate policy responses to the health effects of its products. The approach above allows the gambling industry to be seen as a legitimate policy actor, with the regulator legally obliged to consult the industry when planning the governance of its practices and products.68